Summary

Environmental artist Andrea Polli is driven to create artworks that explore the relationship between air, technology and climate change. From ‘Soundwalks’ in Antarctica to public light installations in Pittsburgh, Polli’s work uses environmental data to help visualise atmospheric pollution through sound and light, with the goal of raising awareness and inspiring action. Her work emphasises the potential of art and technology to address climate change and promote environmental justice.

Reading time

Eight minutes

Environmental artist Andrea Polli creates artwork that gives stunning form to the air we breathe, the sounds we hear and the air that surrounds us all.

My personal and professional relationship to technology, industry and environment is complicated. I grew up in a working-class, second-generation immigrant family who made their living through foundry work. While this gave me a respect for industry, it also meant that, like many low-income neighbourhoods across the world, mine was saturated with the pervasive, sickly smell of industrial waste. At times, it felt like the air was unbreathable but, incredibly, the adults around me never seemed to notice, and this made me wonder. That was how I first realised that noticing is a skill, and to notice the invisible, tiny, subtle or fleeting moment became central to my artistic motivation, leading me to create artworks that raise awareness of climate change and other complex environmental and social issues.

To achieve this, my work explores the potential shapes and intelligences of air through sound, light and other materials in order to express: the fragility of life through the atmosphere/air we breathe; materials and actions invisible to the human eye; and technology as a bridge between breath on a human level and air on a geologic scale.

Above: Andrea Polli in flight to Cape Royds, Antarctica (top), Antarctic researcher Hassan Basagic downloading data from a weather monitoring station on Taylor Glacier (middle) and participants on a Soundwalk led by Polli at McMurdo Station, Antarctic (bottom).

Soundwalking

My first art/science collaborations were with atmospheric scientists, and focused on sonification of weather model data inspired by the soundscape. They were based on the experience of a soundscape as immersive and centred on the listener, who is inextricable to a soundscape experience. To understand soundscapes, I joined the World Forum for Acoustic Ecology, formed by R Murray Schafer, Hildegard Westerkamp and others over 50 years ago. Westerkamp invented ‘Soundwalking’ as an embodied method of personally connecting with the soundscape through focused listening while physically moving through space. The purpose of a Soundwalk is to listen deeply to an environment, whether a pristine natural setting, busy city street, shopping mall or subway.

Before data space existed, humans looked at, listened to, felt and smelled the environment with the goal of prediction. Today, a vast amount of energy and resources are given to the creation and maintenance of computer forecasting models. I wondered, if sonic experience of space is embodied, how can modelled and predictive spaces that are scaled much larger or smaller or of durations much shorter or longer than those we can experience with our bodies, be communicated? Qualities of air, wind, light and humidity have emotional effects on people immersed in atmospheric events. I wondered, can the sound that interprets atmospheric data also have an emotional effect?

A US National Science Foundation Artist’s Residency in Antarctica in 2007/08 gave me a chance to explore this question deeply. I was able to record the Antarctic soundscape, the sounds of wind travelling through glacial ice or of the machines used by research groups to survive in the harsh terrain, and to sonify the data being collected. Many of the scientists I worked alongside and learned from in Antarctica expressed concern about increasingly rapid changes in climate and ecosystems across the continent. Unfortunately, their work had become highly politicised.

As a response, I created an album called Sonic Antarctica, which included a mixture of recordings of the scientists’ words and expressions of concern and the soundscape and sonifications of the data they were collecting. The goal was, in a small way, to give their research a broader reach.

Environmentally responsive public artworks can empower communities and encourage dialogue about local issues.

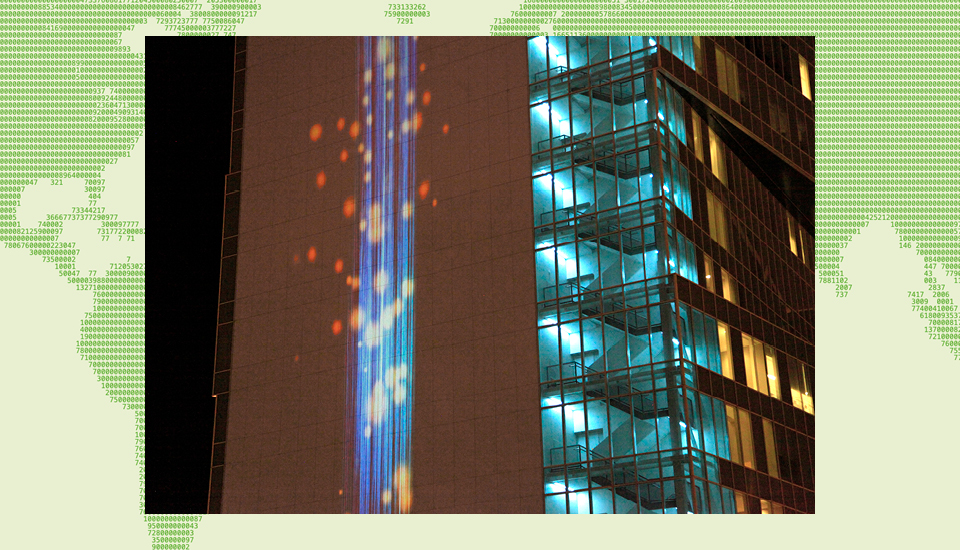

Above: Particle Falls during a high pollution moment in Charlotte, North Carolina, 2021.

Particle Falls

Along with my sonification projects, I began creating animated visualisations of the data with which I was interacting. I soon found that these environmentally responsive public artworks can empower communities and encourage dialogue about local issues. In 2009, I created Particle Falls, a real-time, environmentally reactive public artwork that allows viewers to see current levels of fine particulates as a digitally generated waterfall cascading down the facade of selected buildings (such as theatres, college campus centres and factories). Fine particulate matter is a form of air pollution, the smallest measuring 2.5 microns or less in diameter — just 1/30th the width of a human hair — and called PM 2.5.

Sources of particulate pollution include cars, trucks, diesel buses and construction equipment, agriculture, industry and biomass. There is no safe level of PM 2.5. These particles are so small that lungs cannot cough them out; they contribute to a long list of serious health problems including asthma, heart and lung disease, cancer, adverse birth outcomes and even premature death.

Particle Falls responds to this threat by translating real-time PM 2.5 from the surrounding air into imagery. Fewer bright particles over the waterfall mean fewer particles in the air. The more dots of colour, the more particles there are in the air you’re breathing until, at dangerous levels, the waterfall transforms into a fireball. For example, Particle Falls responds dramatically when a diesel-powered vehicle idles nearby. So far, Particle Falls has been shown in four US cities and at sites across North Carolina, Utah, Germany and France.

Air has been a metaphor for the soul and spirit throughout human history. It carries complex sounds and smells, and holds living genes and atomic histories.

Above: Energy Flow, 2016–2018.

Power projects

While communicating data about climate change and environmental issues can help to encourage public understanding and action, I also wanted to create work with a direct impact. I had a longstanding desire to find ways to actually decrease emissions through public artworks and to use renewable energy to enhance urban aesthetics. Could clean energy not only improve our air, but increase our enjoyment of our cities?

In 2016, I was given the opportunity to create a wind-powered artwork on the Rachel Carson Bridge in Pittsburgh to celebrate the city’s bicentennial. A local wind energy provider, WindStax, designed 16 custom vertical axis wind turbines that generated power efficiently and were also safer for wildlife. The power generated by the wind lit 27,000 LED lights outlining the bridge, and allowed me to add animated visualisations communicating wind energy potential in real time.

In the weeks before Energy Flow was to open, I presented Particle Falls in Paris in conjunction with COP21 and returned home overjoyed by the historic Paris agreement. Not so the US administration at the time. Soon after I completed Energy Flow, the then President tweeted “…I was elected by Pittsburgh not Paris.” Almost immediately, the Pittsburgh mayor’s office asked if I could help the city show support for the climate agreement.

Energy Flow was designed so that I could instantly update the animations from wherever I was, and I was able to send a special design within 24 hours. That experience helped me see a thread that connects people in Paris, Pittsburgh and across the world through public art and shared concerns about climate change and environmental justice.

Translucent medium

Air has been a metaphor for the soul and spirit throughout human history. A translucent medium of exchange between breathing bodies, air carries complex sounds and smells, holds living genes and atomic histories. It contains essences of place and feels and tastes distinctly differently in various geographies, and can have a major impact on human and ecological health.

Above: N-point presents a timelapse of webcam images from the Arctic combined with a four-channel sonification of weather at the North Pole.

In the years I have been working with air, technologies able to sense the complex chemistries and movements of air have evolved dramatically. We can now monitor precisely what is in our air and how it travels, and can use that information to protect ourselves and our environment.

This high-level monitoring and analysis could provide us with a clearer way forward for reducing pollutants including greenhouse gases, and for mitigating negative effects of climate change — for example, better controlling wildfires by closely tracking the movement of wind or designing traffic control signals that can respond in real time to changes in air quality. My current work combines contemporary computation and chemistry in sculptures that give tactile, physical form to the seemingly formless particles and vibrations of air.

Professor Andrea Polli holds appointments in the College of Fine Arts and School of Engineering at the University of New Mexico, where she holds the Mesa Del Sol Endowed Chair of Digital Media. Her artwork and research have received major support from the US National Endowment for the Arts, US National Science Foundation and the Fulbright programme, among others.

This feature first appeared in RSA Journal Issue 3 2024.

pdf 4.7 MB

Read more features from the RSA Journal

-

Ideas Foundation: eyes wide open

Heather MacRae

The Ideas Foundation provides opportunities for students in less advantaged schools across the UK to build creative and cultural capital through workshops and excursions. Their mission? To nourish a new creative generation.

-

Community banking: shared interest

Priya Sippy

Community banking is a microfinance model built on trust. In it, the community wins or loses together. It is gaining in popularity on the African continent as community banking goes digital.

-

Loyd Grossman: secret sauce

Nicholas Wroe

New RSA Chair Loyd Grossman talks music, art and societal change, and why he thinks the work and mission of the RSA is more important now than ever.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.