A regenerative world? What does that mean? This has been a recurring question from our community of Fellows, partners and colleagues since we launched our Design for Life mission in early 2022. Here, Director of Design & Innovation Joanna Choukeir, seeks to answer that very question.

With the RSA embarking on a cross-organisational mission that is at the heart of all we do, it’s everyone’s business to authentically understand the North Star of that mission. From our impact programme and partnerships, to our 31,000 strong Fellowship network, to our assets - people, platform, heritage and RSA House - we all need to, through our collective work, know how to be, how to think and how to act to enable a more regenerative world.

Missions lay behind some of the biggest innovative leaps forward of the last century and can offer the transformative approach needed today.

So, following various iterations, and, bearing in mind there will likely be future evolutions of it, this is where we’ve settled for a working definition of regenerative impact:

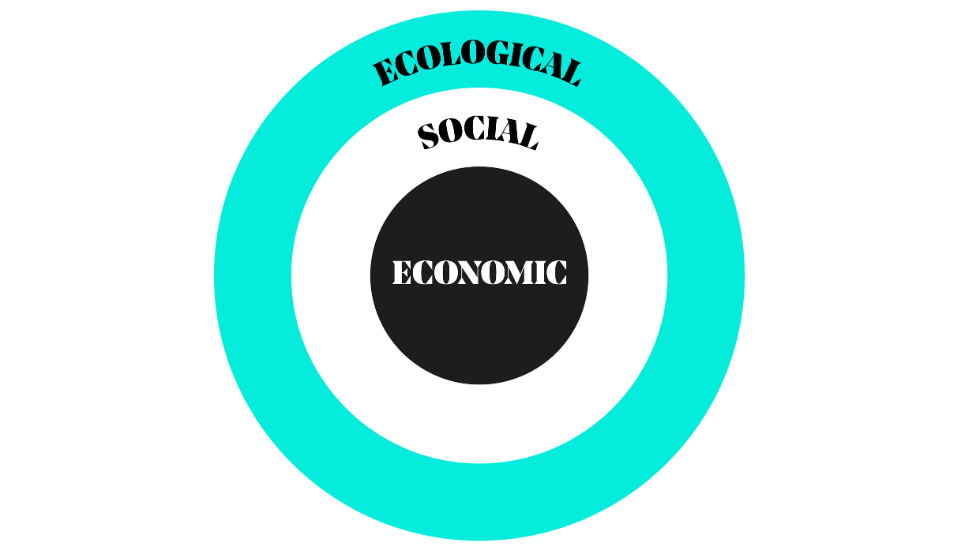

Tangible progress towards improving the health of our interwoven social, ecological and economic systems and their ability to restore and replenish one another. This moves us forward from the passive 'do less harm' principle of sustainability, to the active ‘do more good’ principle of regeneration.

In drawing out distinctions between sustainable, restorative and regenerative impact, we were inspired by the work of a host of practitioners who have trailblazed regenerative practice in recent years. We acknowledge that some of the wisdom behind these practices has been inherent within indigenous communities around the world, who have lived and worked in more harmonious ways with and as nature for centuries. Some of the mental models and frameworks we explored included:

- Bill Reed of Regenesis Groups’ Trajectory of Environmentally Responsible Design

- Carol Sanford and Ben Haggards’ Levels of Paradigm

- CLEAR’s The Lenses Rubrics

- Josie Warden's Regenerative Futures paper.

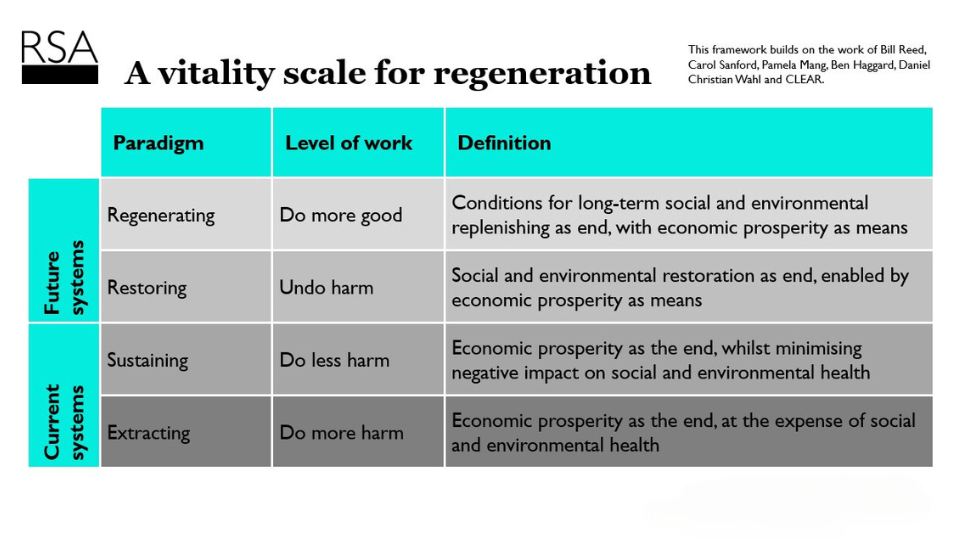

The vitality scale

Building on all this work, we have adapted a framework that we refer to as the ‘vitality scale’. This will guide us to continue stretching our ambitions and practice to be more regenerative. By vitality, we literally mean how alive the systems we’re designing are as informed by living systems principles.

A Vital Scale for Regeneration by The RSA is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

The movement through the scale often involves a gradual progress from one level to the next. We can take soil regeneration for example as an ecological metaphor for our social and economic systems.

The soil metaphor

Regenerating soil that has been depleted through extractive farming practices needs a staged approach across the vitality scale. First step is to take a sustainable approach by doing less harm. This means gradually reducing fertiliser use and soil disturbance methods such as tilling. Simultaneously restorative practices can be introduced to start to reverse harm, such as gradually introducing organic matter and cover crops to improve the nutrient density of soil and to reduce erosion. From there regenerative practices can be established such as improving plant diversity and integrating livestock so the whole ecosystem is continuing to naturally nourish the soil and improve its water retention which in turn, over time, improves the soil’s productivity and the quality of yield – creating a fully regenerative system.

Let’s define each paradigm, or level, and bring them to life using a placemaking example. Excitingly, these levels of thinking can be applied to interventions of any nature, beyond placemaking – such as for shaping policies, transforming organisations, or designing products and services.

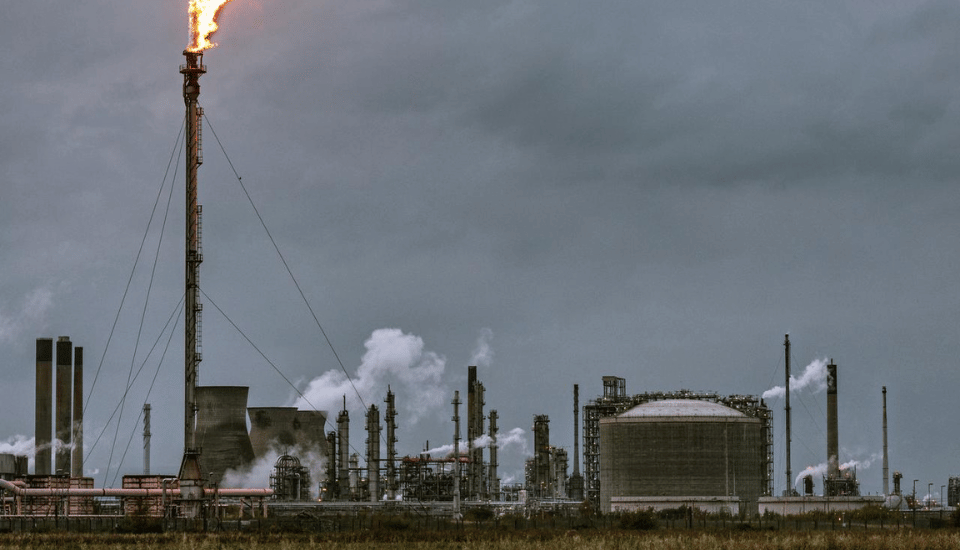

Extracting

This paradigm came forth during the industrial revolution and is still the mainstream approach we take when making everyday decisions about our businesses, places and policies today. Societally, we are continuously improving the efficiency and productivity of the context we’re working in, so we can extract more economic value from that context more quickly. In placemaking, the economic prosperity of a city becomes paramount and the highest form of value desired.

An exploitation of human and environmental capital to achieve economic goals is seen as an acceptable trade-off by those leading and investing in the work. However, any prosperity is short-lived as ultimately the vitality of the place is compromised without a healthy community caring for it, and a healthy ecosystem supporting that community – from clean water and air, to biodiversity and therefore food security. For example, many cities around the world have seen rapid development in the last 20 years, with the growth in value of real-estate investments.

Dubai, from a desert backwater port whose main industry was pearl hunting in the 18th and 19th century, transformed into one of the fastest growing cities with the third-most skyscrapers in the world since oil was discovered there in 1966. And despite its recent transition from a predominantly oil-based economy to a service and real-estate economy, its shiny glass towers stand against a range of social and environmental challenges. Hundreds of thousands of migrant workers were exploited illegally to build the towers, socio-economic divides mean that some of the poorest and richest people in the world are living in the same city, high consumption rates led to the highest per capita ecological and waste footprints in the world, over-fertilisation and soil degradation is leading to desertification, and overfishing and land reclamation is threatening biodiversity.

Sustaining

This paradigm came with the modern environmental movement of the 1970s. The paradigm advocates for doing less harm, to continue improving the productivity and efficiency of the current system. In placemaking, a strategy might prioritise keeping local communities and ecologies healthy enough for the local economy to continue to grow.

However, over time, doing less harm is still doing harm albeit more slowly, and is still depleting the social and natural fabric that places need to thrive. That’s because in sustainable systems, we are often patching up over existing extractive systems to slow down or offset the damage done, when often we need to dismantle existing systems and regrow them differently to do more good by design.

For example, if we take any significant modern urban development of the last 10 years, it would likely have involved total demolition of old infrastructure releasing huge amounts of carbon, and the provision of a diversity of services and infrastructure to support the wellbeing and economy of a community, from housing and health centres to high streets and leisure centres. It would also likely include manicured parks and net zero interventions such as carbon offsetting schemes, partial solar supply systems and electric vehicle charging points.

These place projects though, are not re-designing local jobs and industries to keep people healthier for longer, rewilding green spaces to delivery higher value ecosystem services, reimagining urban mobility away from vehicle dependency, or innovating fully renewable closed-loop energy systems as close to source and consumption as possible. There lie opportunities to shape our future systems as we progress towards the restoring and regenerating paradigms.

Restoring

This paradigm encourages us to try, where possible, to reverse some of the harm done to people and nature through past extractive practices. In placemaking, this might involve valuing the health of the community and environment and trying to restore and retain that health for as long as possible, while recognising how that would drive the economic prosperity of the place. An example initiative in this paradigm is The 3 Cities retrofit.

This project is accelerating retrofit activities across thousands of social homes in the UK between Birmingham, Wolverhampton and Coventry. This allows the pooling of expertise, financing and assets across the diverse housing portfolio of the three cities. The project goes beyond retrofitting existing housing stock which improves residents’ health and the energy efficiency of their homes. It also works to decarbonise heat through district heating networks, and even further downstream to generate local renewable energy through solar and wind sources to fully meet demand.

Regenerating

This paradigm strives to do more good, in the sense of creating the enabling conditions for life to continue to flourish in the long term. In placemaking, communities live in harmony as part of this naturally regenerating ecosystem, and our economic prosperity is continuously reinvested to support the whole ecosystem to continue to regenerate. Examples of modern-day regenerative placemaking are still in their infancy and we are continuing to learn and innovate in this area, not least through our UK Urban Futures Commission. However a couple of promising case studies to point to are The Phoenix in Lewes, and The Wendling Beck Environment Project in Norfolk.

The Phoenix is a proposal to transform a 7.9-hectare brownfield and neglected industrial site within the South Downs National Park to a new and regenerative way to make a place. The development is truly holistic: it will rewild green spaces to improve habitats for wildlife, create river flood defences, provide much-needed jobs and homes constructed from sustainable timber, prioritise people over cars, be powered by renewable energy, and promote a sharing and circular economy.

Wendling Beck on the other hand is a cutting-edge rural project regenerating 2,000 acres of land in partnership with local authorities, landowners, farmers, and environmental charities. It is restoring land and waterways, improving biodiversity, sequestering carbon, and transitioning farming methods to improve long term food security in the region. The project will be innovatively financed through the sale of ecosystem services into nature markets.

Scaling up vitality

This vitality scale will continue to help us stretch the ambition of our work, build bridges and plan just transitions from one level to the next depending on context. It will also support us in continuing to question what we’re valuing first and foremost and what we are prepared to trade off in the short, medium and long term. If you’re passionate about and working in regeneration we hope the framework is useful for your mission as well.

If you’re a Fellow and would like to find our more our Design for Life mission and recent thinking, join our community on Circle.

Discover Circle

Bringing Fellows together in collaboration on their innovations and our mission.

What is RSA Fellowship?

The RSA has been at the forefront of significant social impact since 1754. We invite you to be part of this change.

UK Urban Futures Commission

Unlocking the potential of UK cities, to drive economic, social and environmental improvements for people and for the country.

Read other Design for Life blogs

-

Counting the cost of bowling alone

Blog

Andy Haldane

In his 2025 CEO Lecture, Andy Haldane addresses how the ever-increasing cross-border flows of goods, people and information affect widening divisions and accelerate the depletion of social capital.

-

Prosperous Places: creating thriving communities

Blog

Tom Stratton

With regional growth at the top of the agenda, it is vital that we create thriving communities across economic, social and natural perspectives. Prosperous Places is a suite of interventions aimed at responding to the unique ambitions and challenges of places.

-

From the era of anxiety to an age of aspiration

Blog

Andy Haldane

Shifting to an age of aspiration requires an environment where risk is seen as an opportunity, the culture is one of optimism, and investment is everywhere. Andy Haldane, RSA CEO, suggests our Design for Life mission can turn the tide of opinion to achieve those objectives.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.