Tori Flower is Creative Director of Shift (formerly We Are What We Do), a behaviour change organisation that designs products for social change. She also set the RSA Student Design Awards 'Everyday Well-being' brief in 2013-14 and 'The Daily Diet' brief this year. In a series of seven short blogs aimed at student designers released each day this week, she shares her insights into how to approach designing for behaviour change.

Tip 1: Identify the Actor, Action, Outcome

A great place to start in designing a behaviour change intervention is to identify the Actor, Action and Outcome. This is an idea articulated in Steve Wendel’s brilliant book Designing for Behaviour Change. Other designers sometimes use different terms, or have similar but different starting points for designing, but I have found this approach very useful.

Outcome – This is what you are aiming to achieve and should link back to the social problem you are trying to tackle. It is the change in the world that needs to happen. Outcomes should be specific, unambiguous and easy to measure.

Avoid changes in states of mind as these are difficult to measure and not an end in itself. For example, a student recently came to me aiming to design an intervention in order to bring about “A reduction of sexism”. My advice was to change her desired Outcome to something like “Women and men paid equally by employees for equal work in 100 percent of cases” or “Reduction in number of sexual harassment cases reported by students at a university.” Sometimes adding parameters is also useful - for example a geographical area or a timespan.

Actor – This is the person who will perform the Action. It usually is the user of your intervention. We use the single word “Actor” but this really refers to a group of people. It might be a very large group – like “All drivers in the UK” – or much more specific, like “Year 10 boys at St Martins School”. You are going to need to do research to understand this group of people, so make sure you can get access to them in some way.

Action - This is the single thing that the Actor must do. When the Actor undertakes the Action it causes the Outcome. Your intervention should enable and encourage the Action.

For example, the Outcome might be "People stop smoking cigarettes", the Actor "Adults aged 18-40 in the UK" and the Action "Actors replace cigarettes with nicotine replacement therapy chewing gum".

Actions should be concrete and specific. They should be both small enough to be manageable for the Actor, and big enough to have a definite impact on the Outcome.

Avoid an action that just affects the Actor’s mental states:

e.g. Actor respects their grandparents more - not so good

e.g. Actor telephones grandparents once a week - better

The Action should have a direct effect on the Outcome

e.g. Action: Actor attends a seminar on reducing food waste - not so good, as this may or may not have an effect on the Outcome: Reduction in amount of food each house wastes.

e.g. Action: Actor use all leftovers from dinner for lunch the next day - better

There maybe several Actions that could lead to an Outcome

e.g. If the Outcome is “Actor loses weight”, the Action could be:

-

Actor does 30 minutes of swimming a day

-

Actor walks to and from work everyday

-

Actor replaces high sugar drinks with water or diet alternatives

-

Actor doesn’t eat between meals

Start by writing down a long list of possible Actions. To generate this list, ask yourself:

-

What is the Actor currently doing which brings about the Outcome?

-

What are others doing which brings about the Outcome?

-

What Actions are they doing which bring about the opposite of the Outcome? How can you reverse these?

Note that positive Actions (e.g. Actor replaces high sugar drinks with water or diet alternatives) tend to be easier to design for than negative ones (e.g. Actor doesn’t drink high sugar drinks).

Generally selecting a single action is best, especially to begin with as it leads to more simple and effective interventions. When you are assessing which Action from your long list to pick, think about:

-

Which Action will have the biggest impact on your Outcome? (e.g. It would take about three hours of fast paced cycling to burn off a whole Dominos pizza, so Actions which target dietary changes may be more effective than exercise-based ones, if the desired outcome is weight reduction).

-

Which ones are your Actor mostly likely to do? (See my next blog on identifying Motivations and Barriers and using this to compare Actions against each other)

-

Which Action it is feasible to design for?

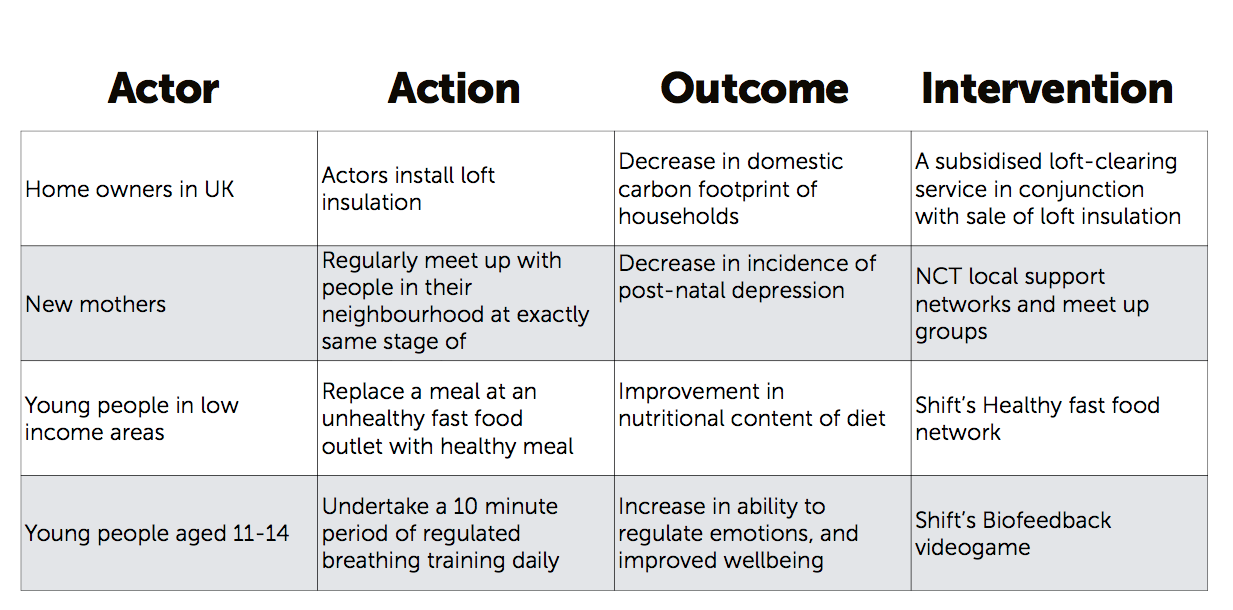

Examples of Actor, Action, Outcome

These are taken from existing interventions designed by Shift or other organisations working in behaviour change.

Applying this to your work

You may be answering a specific brief, in which case draw out the Actor, Action and Outcome from the information given to you. Alternatively, you may be writing your own brief, in which case this is a useful framework to clarify your intentions.

In my next blog

Tip 2 - I’ll explore how to generate a really clear understanding of what the Actor’s barriers are to undertaking the Action, and what might motivate them to undertake it.

>> Find out more about the RSA Student Design Awards

>> Find out more about Shift

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

Hi Tori - whilst I like the article and agree with it in the main, a functionalist bias seems to write off solutions which have worked well in many non-functionalist strategies.

I'm only a partial believer in dividing people into types, but sometimes it is helpful or even necessary. Certainly for those whom practiced the arts, apparently especially music, early in life one facility developed is that of more greatly connected intelligences and another, partially developed through values-based discussion (but having other sources, too), is stronger link-dependent behaviours. Such 'types' of people require either reason and/or understanding for motivation towards outputs and thus straightforward statements of outcomes will be too simplistic or unattractive - either way will not be motivational and thus will be ignored or rejected.

The usual will apply - everyone needs to be treated as whom they are and respected, understood, coached/coaxed from this place. Whilst your Part 2 will no doubt cover this, rejection happens at the ideas creation stage when ownership takes place and this ownership can be built into Part 1, saving effort and/or failure later.

Amongst the millions of human 'types systems' available, the most useful I've come across to date is that of 'Empathy' <http://www.lifecollege.org/Lifecollege-Empathy.html> which seems to work - whether leading, managing or selling ideas/change by meeting the origins of motivators head on and thus overcoming the deeper blocks sooner and thus less expensively.