Summary

This article highlights the growing influence of AI on society and the environment, focusing on the opportunities and challenges posed by large-scale AI models. Big Tech is at the forefront of the development of broader AI technologies, as well as particular AI climate tools. While promising, this evolution demands significant energy and resources. The piece calls for greater transparency and responsibility in AI’s development, and explores whether the potential benefits to the planet outweigh the environmental risks.

Reading time

Nine minutes

From deforestation detection to disaster response, AI applications developed by Big Tech show promise – but at what cost to our environment?

The lives of most of today’s adult generation have been shaped by access, or lack thereof, to the internet and mobile connectivity. When we consider the role of this infrastructure in our lives, we likely think about our use of services such as email, cloud storage, search engines, GPS maps, social media, video streaming and e-commerce — the tangible representations of our digitised world.

Thirty years into this digitised future, we face another watershed moment. Over the last year, a slew of popular applications have become key entry points for most people to experience artificial intelligence, or AI. ChatGPT’s text-generation tools, image generators such as Midjourney and DALL-E, and chatbots on search engines and social media are shaping what AI is to us and beg the question: if today’s ‘AI’ can do anything — from summarising search results or planning a vacation to content generation — with a few simple prompts, what will it be capable of in the near future?

Understanding AI

This is the question being asked across sectors. For example, lately, several reports have attempted to predict how AI can bolster environmental protection efforts and tackle climate change. To understand the possibilities and problems with using AI for this goal, we first need to demystify and redefine AI and rid ourselves of the pernicious idea that the AI industry’s trajectory is inevitable — and that we must accept the trade-offs that come with it.

AI has been transforming climate technology for years now. We hear about this less in the media because the type of AI that climate technology has been harnessing is less ‘sexy’ than ChatGPT and other similar products, which rely on a large-scale AI model. This type of large-scale AI (also known as a ‘foundation model’) is trained on massive amounts of data and requires robust computing power to support a variety of end-user applications that run on top of it. As flexible as these models are, they come with downsides: because they gobble up so much data and can be used for so many different purposes, the models are prone to produce inaccurate content or they fail at the tasks they are asked to perform.

Large-scale AI has attracted attention because it teases the idea that computers are fast approaching human-like intelligence. There is no likely future scenario in which this will happen. This mistaken and widely discredited belief (despite the obsession of numerous billionaires with promoting it) obscures the fact that there are other types of AI worth harnessing, and it distracts us from thinking critically about what exactly the purpose of developing AI truly is.

Yes, large-scale AI can certainly collect and categorise patterns of human-generated input and automate its ‘learning’ process to respond to human-generated prompts. But while it may be fun to think of how this could evolve into Terminator-like androids and ‘sentient’ machines, this is science fiction. As computer scientist and author Meredith Broussard puts it in her book Artificial Unintelligence, what we have today is “narrow AI”, which focuses on statistical models and augmenting data processing to solve specific tasks.

Technology only acquires meaning by how it is used, by whom, and the problems it solves.

To understand the possibilities and problems with using AI to tackle climate change, we first need to demystify and redefine AI and rid ourselves of the pernicious idea that the AI industry’s trajectory is inevitable – and that we must accept the trade-offs that come with it.

Harnessing climate technology

To redefine AI, we should remember that technology only acquires meaning by how it is used, by whom, and the problems it solves. Machine learning, a form of narrow AI, has multiple applications in climate technology. A particularly impactful one focuses on bolstering existing efforts to prevent deforestation of the Amazon rainforest by involving affected local communities.

Preserving the Amazon is a complicated task, particularly given the challenges to on-the-ground access. Forest monitoring systems such as the Global Forest Watch work with advanced sensors that rely on machine learning to detect changes in images, identify ‘hot spots’, and issue deforestation alerts, a process known as ‘remote-sensing technology’. On the ground, combating deforestation often entails shoe-leather policing by Indigenous communities, who confront and deter invaders seeking to use protected areas for logging, mining and farming. The problem has historically been, and remains, that this technology does not reach these communities at scale.

In 2018, a study led by researchers from New York University and Johns Hopkins University, involving a group of Indigenous communities in the Peruvian Amazon started to bridge that gap. The project, facilitated by Rainforest Foundation US, focused on training forest monitors and local communities to use a mapping app that collected alerts, helping them locate forest disturbances and intervene against offenders. The results, published in 2021, provided valuable evidence for the potential of remote-sensing technologies: deforestation in these communities dropped by 52% in the first year and 21% in the second year, compared with communities who did not participate in the project.

More recently, in Brazil, a new AI-powered project is taking remote-sensing technology a step further to produce faster and more frequent updates on high-risk areas prone to deforestation. Using satellite images from the European Space Agency, as well as historical and topographical data, an app called PrevisAI can automatically detect clandestine roads, which are a key predictor of deforestation. PrevisAI is already helping Indigenous communities in the state of Acre to deploy a proactive patrolling strategy that includes the use of drones. The project was developed by the non-profit Imazon using Microsoft’s cloud computing product Azure.

Dealing with the destruction wrought by extreme weather phenomena is also key for climate change adaptation. One challenge for first responders is how to quickly locate severely impacted areas to assess damages, including damage to infrastructure. To address this problem, in 2019 the US Department of Defense and NASA launched xView2, a program that brought together several companies and researchers to harness machine learning AI and big datasets to more quickly identify damaged buildings. With a success rate of 80% in damage assessment, algorithms developed under this program were used to assist with the 2020 California wildfires, and the 2019–2020 Australia bushfires.

Across the board, efforts to employ AI to tackle climate change are inspiring scores of useful applications, such as improved forecasting of extreme weather events, speedier identification of melting icebergs, tracking of carbon emissions, clearing plastic pollution from the ocean and predicting the output of renewable energy sources.

With the understanding that we need to tread carefully to determine where AI systems can be trusted to perform reliably, these projects can speed up responses from governments and local communities to allocate resources where they are most needed. Measuring real-life impacts of these systems could also inform and embolden regulators to implement more effective oversight of environmental practices in critical sectors, such as agriculture, fishing, mining, electricity and the technology industry itself.

To redefine AI, we should remember that technology only acquires meaning by how it is used, by whom, and the problems it solves.

Feeding the machine

We cannot ignore another competing reality: the bulk of the AI industry is moving in the direction of large-scale AI models. Big Tech companies are in a race to make a business case for commercially deploying large-scale AI, and their push to embed these models in anything and everything demands the construction of massive data centres — and the power to run them.

The development of large-scale AI requires: infrastructure, represented by the data centres that cluster chips to support supercomputers for AI training; hardware, which is the design and fabrication of the chips that provide computing power; and software, understood as the programs that enable companies to use these chips to build foundation models that make AI end-user applications work.

Amazon, Microsoft and Google have data centres that provide two-thirds of the cloud and computing services globally, so they are specially equipped to host supercomputers. They also provide AI foundation models. This means that they sit at the intersection of infrastructure and software. Other familiar names, Meta and OpenAI, also compete in the software space with their own foundation models and end-user applications. As if this weren’t complicated enough, OpenAI is financially and operationally backed by Microsoft, and in a similar way Anthropic — a competitor of OpenAI — is backed by Amazon.

Clearly, a handful of large corporations are in a key position to shape the future of AI and its role in society, affecting not only how large-scale AI will be used, but also how transformative other types of AI can be. Right now, in order to make any AI-powered initiative possible — narrow or large-scale AI, whether AI training runs on a laptop or a supercomputer, for commercial or personal purposes — it all depends on the same resources: access to infrastructure, hardware and computing power. What varies is the intensity with which we are using each of those resources.

For AI to be a powerful and effective component of a courageous approach to climate change, there first needs to be transparency and accountability.

Powering the future

This is where it gets trickier. Even when considering some of the most impactful ways in which other types of AI are driving solutions for our planet, sustaining the dominant AI model is putting enormous pressure on global energy supply. A Bloomberg investigation estimated that if we continue at current levels, by 2034 the global energy consumption by data centres would top 1,500 TWh, about as much as the energy used by India in all of 2023. News reports (including a June 2024 item in The Washington Post) show some US states are abandoning or delaying the shutdown of coal units to prevent further destabilisation of the power grid driven by the energy demands of Big Tech.

Tech corporations are fully aware of the environmental impacts of their operations. Google and Microsoft aim to run their data centres on green energy by 2030, and Amazon by 2025. Yet, since setting their net-zero goals between 2019 and 2020, the three tech giants have increased their carbon footprint, on average, by 37%. On a yearly basis, only Amazon, out of its peers, saw its carbon emissions slightly decrease in 2023.

Executives of these corporations assure us that, in the long run, the benefits of AI will outweigh the harms if we just “speed up the work needed”, as Brad Smith, President and Vice-Chair of Microsoft, said in a May 2024 Bloomberg piece. Yet the “work needed” in their view, seems to be a wish list of breakthroughs that would materialise at some point in an undetermined future, such as if clean energy from nuclear fusion or geothermal power sources became readily available and abundant.

The question then becomes, considering the climate technology projects that Big Tech either directly funds or supports through partnerships, whether the footprint of their business model is already watering down the impact of such projects?

We are at the beginning of a collective journey to redefine AI and its purpose in society. This is a conversation in which we should all play a part.

Recommended reading

"Climate Capitalism by Akshat Rathi makes you think deeply about capitalism’s place in our transition to a greener world. Using examples from five continents, this book teaches us that the climate movement is not only already transforming capitalism, but that it must." Karina Montoya

Making AI sustainable

For AI to be a powerful and effective component of a courageous approach to climate change, there first needs to be transparency and accountability. Despite the sustainability reports and climate pledges from Big Tech, there is currently a lack of standards to measure and mitigate the environmental footprint of AI. A good way to start would be with meaningful disclosure of a series of markers, such as energy consumption and carbon emissions incurred during the lifecycle of the AI model. Researchers Emma Strubell at Carnegie Mellon University and Sasha Luccioni at AI startup Hugging Face have provided stepping stones for a framework on how to do just that.

Luccioni’s study, for example, measured the environmental footprint of a multilingual foundation model for translations called BLOOM, which works with 175 billion parameters — variables that instruct the AI model how to turn inputs into outputs. She found that just training it, which took almost four months, consumed as much energy as 30 homes in the US per year, and that it generated 25 metric tonnes of carbon dioxide, the same as driving a car five times around the planet. By way of comparison, training a model like GPT-3, an OpenAI model with almost the same number of parameters as BLOOM, emitted 20 times more carbon dioxide and consumed almost three times more energy.

Tech companies also need to be transparent about their water consumption, both for electricity generation and cooling of data centres. Estimates show that training ChatGPT in Microsoft’s data centres can evaporate 700,000 litres of clean freshwater, according to a recent study co-authored by Shaolei Ren at the University of California, Riverside. According to the study, the global AI demand may be accountable for up to 6.6bn cubic metres of water withdrawal (water taken from surface or underground sources) in 2027 — more than the total annual withdrawal of half of the United Kingdom.

We are at the beginning of a collective journey to redefine AI and its purpose in society. This is a conversation in which we should all play a part. Advocating for a more sustainable and accountable future for the AI industry can be strengthened by raising awareness of three key dynamics. First, that no technology is developed in a void; it is more important to think about how it will be used and who it will empower. Second, it matters who holds power over the resources that others need to innovate and challenge the direction of dominant business models. Last, but not least, unlike the forces of nature that hold together this Earth we live upon, there is nothing inevitable in human-made systems that we cannot change if they are not working to make our lives sustainably better.

The future of AI is in our hands. We just need the courage to write it.

Karina Montoya is a business and technology journalist. She is currently Senior Reporter and Policy Analyst at the Open Markets Institute.

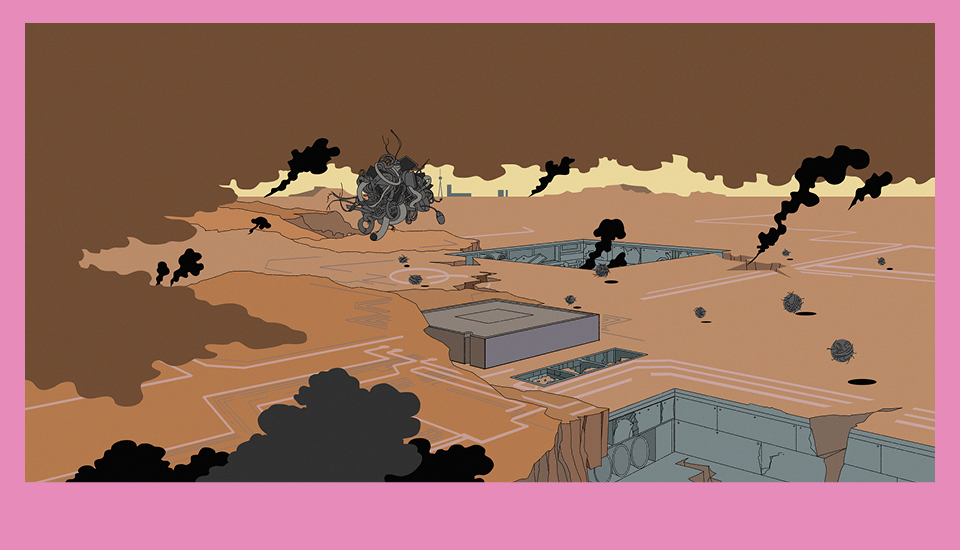

Manshen Lo is a London-based visual artist whose approach to drawing has its roots in East Asia.

This article first appeared in RSA Journal Issue 3 2024.

pdf 4.7 MB

Read more lead features from the RSA Journal

-

Save the the planet, eat the world

Karina Montoya

From deforestation detection to disaster response, AI applications developed by Big Tech show promise — but at what cost to our environment, asks Karina Montoya.

-

Democracy in the age of AI

Audrey Tang

Taiwan’s first Digital Minister, Audrey Tang, highlights the country’s approach to developing safe, sustainable and citizen-led AI as a model to revitalise global democracy.

-

A world without the RSA

Anton Howes

The Society celebrates its 270th birthday on 22 March. But what if it had never been born?

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.