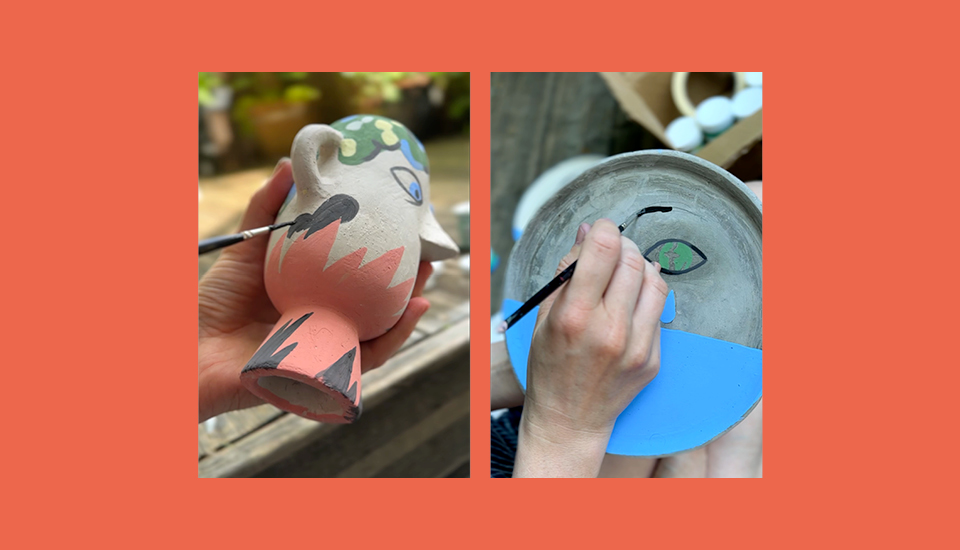

Above: About this piece, artist Tania Yakunova said: “In this piece, I wanted to show how global warming and anxiety around it ruins not only our precious ecosystem, but can harm blooming young minds.”

Summary

This piece, written by Judith Anderson, Chair of the Climate Psychology Alliance, discusses the emotional toll of climate change (particularly on younger generations) emphasising the fears, anxieties and isolation they might feel when dismissed by older generations. It stresses the importance of offering support, validating their concerns and involving them in decision-making. Anderson advocates for realistic hope, collective action and building resilience to address the climate crisis.

Reading time

Six minutes

As the climate emergency intensifies, young people bear the emotional brunt of a crisis they didn’t create. Their anxiety and outrage demand our understanding – and urgent support.

When I heard UN Secretary-General António Guterres say that the goal of holding temperature rise to 1.5˚C is “on life support”, I could feel that in my body and emotions as if I were hearing about a relative in hospital. The message is more than cognitive.

Those facing climate change are living with the existential threats that they know are an everyday reality for people dwelling on low-lying islands, enduring the death-trap of heatwaves or eking out an existence in the face of repeated crop failures. When those around us are not taking the climate and ecological emergency seriously, and governments are not responding to the problem, those who are ‘facing difficult truths’ and working towards mitigation and adaptation may well be undertaking emotional heavy lifting on behalf of others.

There are particular challenges for those in the first quarter century of their lives because they have never known a world without visible escalating climate change. There are many levels of this to disentangle.

A 2021 UNICEF report refers to the climate crisis as a “children’s rights crisis” and says: “Almost every child on Earth is exposed to at least one of the major overlapping climate and environmental hazards.” A greater proportion of children’s lives and those of the communities where they live, as well as the living fabric of the world around them, is certain to be affected by climate change. This inevitably means that they are impacted physically and emotionally by witnessing and participating in the societal disruption of climate-driven events, feeling fear, anxiety, grief, anger and many other emotions about both present and future.

Shockingly, research tells us that when young people express their (completely justified) thoughts and feelings about this, their emotions and opinions are often not taken seriously by those close to them, leaving them to carry this load on their own. This isolation is worsened when, in an abrogation of responsibility, they are told that they are the generation that will have to sort this out! The experience of governments not acting appropriately is an experience of deep neglect, representing moral injury, and coming from what psychoanalyst Sally Weintrobe describes as a “culture of un-care”.

When, perhaps inevitably, outrage at what is happening takes the path of non-violent direct action, environmental protesters – including young people – have lost their lives. On average, over the decade ending in 2022, an environmental activist was killed every two days, according to a report by international non-governmental organisation Global Witness. Such violence is particularly prevalent in South American countries, but deaths in the Philippines are second only to those in Brazil. In Europe, there is increasing violence of various forms by the police against protesters, potentially in breach of the UN Declaration on Human Rights Defenders.

Above: Commenting on creating the artwork to accompany this article, artist Tania Yakunova said: “Ceramic is a very special media and a perfect match for the project. It’s unpredictable. You can only control so much, and even putting all the work into the piece, you still pray to the powers of nature for things to work out right. It’s both very fragile and very strong, just like our brains - and our planet."

There are particular challenges for those in the first quarter century of their lives because they have never known a world without visible escalating climate change.

No illusions

What approaches can assist? We cannot deny young people’s lived reality, nor seek to pretend to them that all is well. When the child of a parent who is seriously ill can see the evidence of their illness and overhear urgent conversations, giving them false hope leaves them feeling isolated, lied to and uncared for.

What we can offer instead is caring, solidarity, validation, empathy and engagement with what troubles them most, plus ongoing support for their concerns and the actions they want to initiate. It is entirely normal for parents and teachers to find the task of staying engaged with young people’s feelings too challenging: we have our own biodiversity of emotions – rage, guilt, grief – and all of the understandable dissociative strategies we have developed to deal with them.

But we cannot walk away from this. There is support and advice available. Some schools run climate staff rooms, a version of climate cafés that can be used to support teachers feeling overwhelmed by climate change or experiencing climate change worries themselves. These can also be used by staff when supporting children who are having similar feelings.

Teaching the syllabus on climate change is not an emotion-free zone! ‘Parent circles’ run by the Climate Psychology Alliance on a regular basis offer a non-judgemental space for parents, grandparents and carers to share their feelings and dilemmas. Jo McAndrews’ Truth without Trauma programme offers practical, creative steps to help those in any parenting role stay alongside children and young people facing the climate and ecological emergency.

In addition to appropriate support, the agency of young people in relation to their futures requires the robust inclusion of youth voices and creativity in decision-making at every level.

What we can offer is caring, solidarity, validation, empathy and engagement with what troubles them most, plus ongoing support for their concerns and the actions they want to initiate.

State of emergency

We are in an emergency, but it is a long emergency, which means that, whatever age we are, we have to approach it with attitudes and skills that will build and sustain resilience for the long haul. Having clear boundaries is vital, and this includes knowing what our own capacities are and saying ‘no’ if the situation or a request exceeds these and ‘yes’ to necessary self-care. We need organisational environments where such boundaries and self-care are encouraged.

We need to discover, through interior inquiry and discussion with others, what our individual skill is, be it speaking to politicians, initiating imaginative activist actions, providing spaces where the bruised and exhausted can find respite, or building local community in more general ways. We also need to make time for mutual support; some activists feel guilty about this, but it is vital to prevent burnout.

We need to build a generation of psychological professionals who are educated about the psychological impacts of climate change and trained in how to work with these both inside and outside the consulting room, in part through understanding their own reactions. The Western paradigm of therapy can be very individualistic, but it is as communities that we face the challenges of climate change.

And we must not forget to find joy as we navigate these times. We might find it in the simplest of places: growing tomatoes on a windowsill, cooking, listening to or creating music, or playing football.

Whatever our calling, we have to keep on until there is a global social tipping point and then work to grow it and maintain it.

Above: Artist Tania Yakunova at work.

Radical hope

I am sometimes asked about hope. People say to me, “We must give young people hope.” All too often that means suggesting that we tell an incomplete narrative, or invoke the certainty that science will solve the problem, or promote the idea that individual actions are an adequate solution. I am not interested in the kind of hope that denies the reality of what we are facing; this is false hope verging on denial. Ideas that nourish and challenge come from those who grasp what it is to hope under very difficult circumstances.

I am inspired by the kind of hope that Rebecca Solnit advocates in her book Hope in the Dark, based on evidence from social justice movements. She reminds us that, “What we do now matters tremendously, because the difference between the best and worst case scenarios is vast, and the future is not yet written.” She focuses relentlessly on the gains, not the losses, and the possibilities if we act now and keep the faith.

Jonathan Lear’s wonderful treatise Radical Hope: Ethics in the Face of Cultural Devastation is also relevant, citing the experience of an Indigenous tribe in America whose entire way of life was destroyed when the buffalo was slaughtered to almost complete extinction, and yet they found a way of maintaining their identity under these most impossible of circumstances.

Václav Havel’s notion of ethical hope sustains me: “Hope is an ability to work for something because it is good, not just because it stands a chance to succeed. The more unpropitious the situation in which we demonstrate hope, the deeper that hope is.” This seems particularly apt given that science tells us every tenth of a degree that we hold global temperature down makes a difference to the escalating tipping points, and to the vicious circle of effects in the wonderfully rich complex systems that create global climate.

So we must not give up. Whatever our calling, we have to keep on until there is a global social tipping point and then work to grow it and maintain it in the same way that democracies and their ideas must always be defended and never taken for granted.

I’m grateful to many colleagues within the Climate Psychology Alliance whose thinking and companionship has enriched my ideas, especially those working and researching the impact of climate change on children and youth.

Judith Anderson is a psychotherapist and retired psychiatrist, Chair of the Climate Psychology Alliance and co-editor of Being a Therapist in a Time of Climate Breakdown.

Tania Yakunova is an award-winning Ukrainian illustrator, ceramicist and educator currently based in London.

This feature first appeared in RSA Journal Issue 3 2024.

pdf 4.7 MB

Read more features from the RSA Journal

-

Community banking: shared interest

Feature

Priya Sippy

Community banking is a microfinance model built on trust. In it, the community wins or loses together. It is gaining in popularity on the African continent as community banking goes digital.

-

Wikimedia: people-powered

Feature

Lucy Crompton-Reid

In an age where knowledge is everything, Wikimedia’s behind-the-scenes communities are keeping the lights on and ensuring the truth is told.

-

Ideas Foundation: eyes wide open

Feature

Heather MacRae

The Ideas Foundation provides opportunities for students in less advantaged schools across the UK to build creative and cultural capital through workshops and excursions. Their mission? To nourish a new creative generation.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.