The Clerkenwell Design Festival is an annual celebration of the creative, seductive power of design. It brings together the experimental and entrepreneurial with the established veterans of the trade in this effortlessly cool corner of the capital. Cornish oysters are consumed, Somerset’s best cider is quaffed and home counties wine flows freely. Showrooms host receptions and the networking elite of the design world are out in force.

Into this realm of style and taste last Thursday came the Great Recovery’s Survivor Sofa, a piece of ‘bulky waste’[1] that had been rescued from a landfill skip in Surrey as part of our recent design residency run in partnership with waste and resource management company SITA UK. The sofa’s previous owners had discarded it after deciding to redecorate and finding that it no longer suited the ‘look’ of their home. It was in almost mint condition, having been bought from Laura Ashley only 2 years before at a cost of almost £2,000. Staff at the Surrey amenity site were unable to find a fire label on it, meaning that it could not be passed on for resale by the local reuse network, and so it was destined to rot away in a hole in the ground – too bulky even for incineration.

Not ones to stand idly by whilst things go to waste, the Great Recovery team persuaded the site managers to let us take the sofa away (research purposes only!) and carted it back to our innovation hub at Fab Lab London. With the help of Hackney’s finest furniture hackers, Urban Upholstery, our team of designers deconstructed this ‘survivor’ sofa to find out just what was in this staple of the living room: as it turned out, hessian, foam, cardboard, birch, plywood, shoddy (recycled jumpers), polyester wadding, steel springs, calico – all held together by hundreds of staples!

It is this kind of action-based research that is so vital to the work of The Great Recovery project. Only by looking inside our everyday ‘stuff’ can we come face to face with the materials that comprise it and the fascinating real-life stories of production, manufacture, travel and waste that lie behind it. As we have heard so often, we can be told something many times without really ‘ingesting’ the information; it is not until we are shown it, and get to experience or do it for ourselves that we really learn and are empowered to create change.

This is the philosophy that we brought to Clerkenwell. Stripped back to its bare birch and ply frame, shivering shyly in the sunlight, the sofa would begin its new life on the streets of London. Not as a fly-tipped piece of bulky waste, but a metaphor for survival, a message writ large and speaking of the possibilities of recovery, the value in our waste, the glint in our glar[2].

As our Urban Upholsterers went about the process of reupholstery and rebirth right there on Britton Street, passers by were drawn in by the process and fascinated by the opportunity of seeing inside a sofa. By taking the mystery out of one of our most common household objects, we had uncovered the magic of manufacture, and materials. We invited designers and the general public alike to help us with the simple process of button making for the sofa base, and several were almost euphoric at discovering their own ability to make a humble button: ‘I’ve never made anything before’, said one. ‘Can I take it home with me?’

All too often, the methods of product making and its counterpart, waste making, are hidden away from view - in factories and in amenity sites and landfills. We make use of the in-between stage for a few months, and then away it goes – to be replaced by another. But by engaging people actively with these systems, showing them how things are made and unmade – and can be made again – we can disrupt these conventional patterns of consumption and disposal. This is something that the Fab Labs and make spaces springing up all over the world have at the forefront of their practice: the empowerment of individuals to create and make for themselves.

The act of making is one of care; we are far more likely to repair something we have made ourselves rather than throw it away, and, as Walter Stahel set out many years ago, the act of caring for our stock resources is integral to the notion of a circular economy[3]. By showing people the way to create, we can not only give them the power to create for themselves but enable them to maintain, or care for, existing creations. And that is what we were doing on the streets of Clerkenwell: creating a caring circular economy. One sofa at a time.

Related articles

-

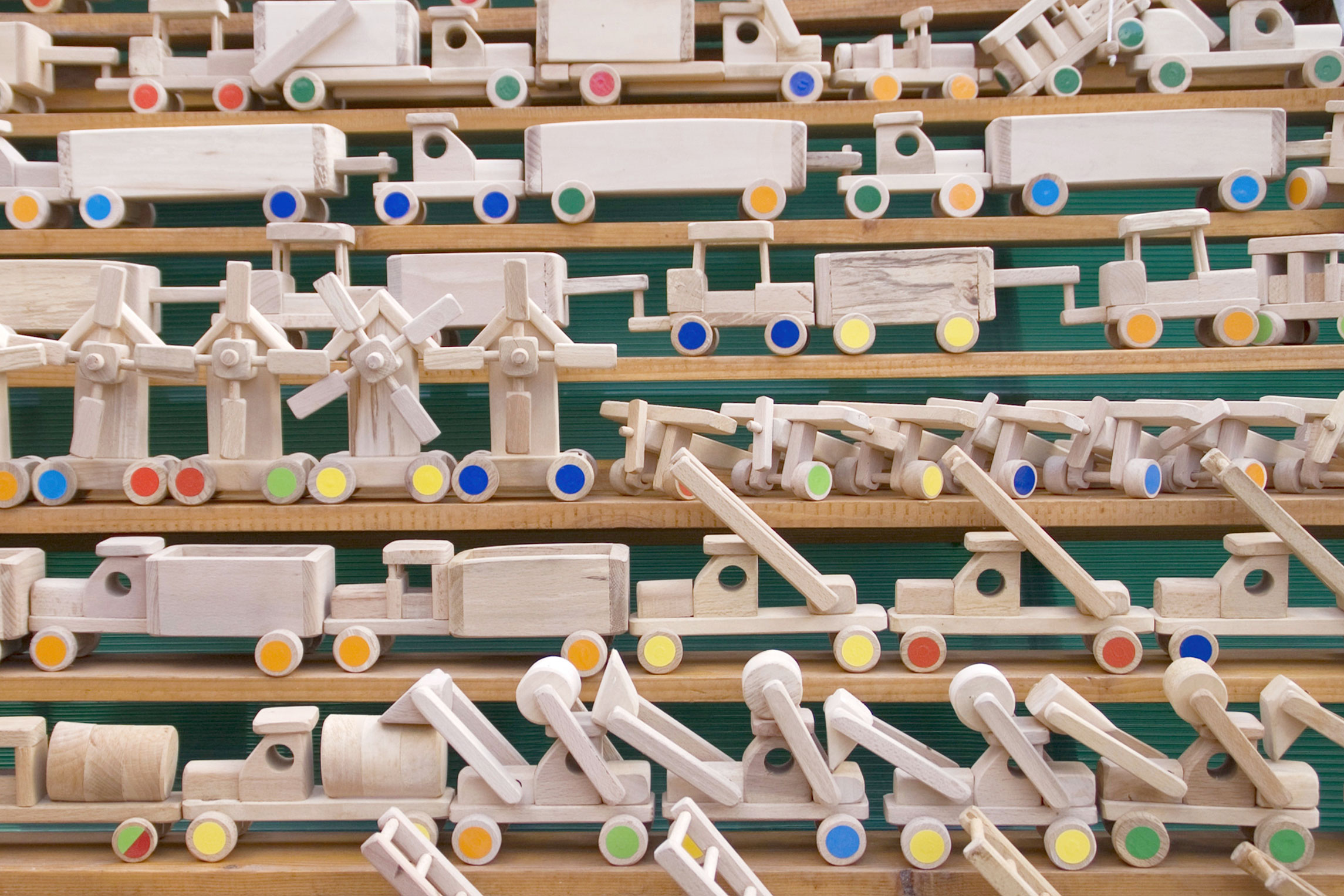

Toying with circularity

Lucy Chamberlin

One of this year's Student Design Award briefs asked students to redesign a children's toy to eliminate waste and reduce environmental impacts.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.