The second week of talks at the United Nations climate conference, COP24, has begun in Katowice, Poland. Delegates from across the world are convening conversations on the future health of the planet and everyone on it, to help governments finalise and implement the Paris Climate Change Agreement. The role of technology in carbon reduction is a major focus of talks, but what part can electromobility play in the goal for net zero global emissions?

Sir David Attenborough gave a stark warning to audiences in Poland as proceedings began last week – climate change is the greatest threat to our planet in thousands of years, "if we don't take action, the collapse of our civilisations and the extinction of much of the natural world is on the horizon." This warning was echoed in the recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report: governments must slash greenhouse gas emissions by 45% by 2030 to keep global temperature rise to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels - a level which mitigates many of the most severe impacts.

It’s clear that a wide-ranging set of interventions are required from all areas of society to implement the required de-carbonisation and ecological safeguarding, but let’s go on a drive down the road to electromobility to explore exactly what it is, the targets, what’s holding progress back, and what the future may look like.

Electromobility?

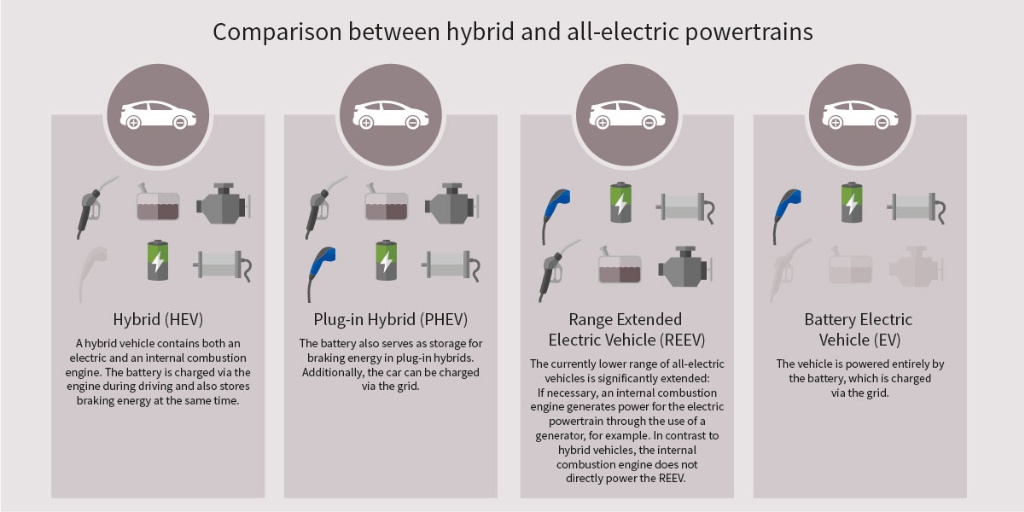

Electromobility, or e-mobility, is a general term for the development of electric-powered drivetrains designed to shift vehicle production away from fossil fuel usage in traditional internal combustion engines. This includes everything from electric and petrol-powered hybrid vehicles to fully battery-powered electric vehicles.

E-mobility has several advantages over traditional combustion engines, the obvious being the vastly reduced, or zero, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions - transportation currently makes up 14% of global emissions, of which around two thirds are road based. As well as warming the planet, exhaust fumes are fast becoming a huge public health problem - more than half the global population was exposed to air pollution levels at least 2.5 times higher than the safety standard in 2016. 90% of urban dwellers are breathing unsafe, noxious air, resulting in 4.2 million deaths per year. A staggering number. The global population living in cities is projected to reach 70% by 2050, so pollution levels will have be drastically reduced for sustainable urban development. Less dependency on imported energy, reduced noise pollution and an opportunity for modern jobs are further advantages of e-mobility.

The targets

Government targets for the roll out of electromobility are a relatively new development. Norway leads the way with a target for all new cars to have zero emissions by 2025, and have been using tax breaks to incentivise purchases since the 1990s. Germany, Ireland and the Netherlands have all set a target of 2030 to ban sales of new internal combustion powered vehicles. UK Government targets state that all new cars will be ‘effectively zero emission’ by 2040, though a report from the Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) select committee suggested bringing the ban forward to 2032 – in line with Scotland’s target. In 2011, the European Commission published a white paper, ‘Roadmap to a Single European Transport Area’ which provided 40 initiatives to build a competitive transport system that will increase mobility, dramatically reduce Europe's dependence on imported oil and cut carbon emissions in transport by 60% by 2050.

Before COP24, and despite international efforts, only 16 countries had acted to phase out internal combustion transportation. However, good progress has been made at talks in Poland, with over 40 countries signing a declaration called ‘Driving Change Together – Katowice Partnership for Electromobility’ - one of the concrete dimensions of implementation of the Paris Agreement and fulfilment of the Global Climate Action objectives. Among the signatories are the UK, China, Japan, Indonesia, Mexico, France and Germany, alongside thirteen international and nongovernmental organisations, including the World Bank and The Climate Group.

What’s holding progress back?

A study this year identified three major areas that are holding back e-mobility;

- Affordability

- Infrastructure availability

- Lack of investment

The market share of electric vehicles is still small and only grew in the EU by 0.9% between 2014 and 2017, with 85% of all EU electric car sales concentrated in just six Western European countries (with some of the highest GDPs.)

To tackle the unaffordability of e-vehicles, Norway has introduced a set of taxes that make buying electric vehicles a sensible financial option. An imported VW e-Golf 36kWh costs £28,285 before taxes, compared to the petrol-fuelled Golf 1.2L at £19,867, however, after a range of taxes and charges the petrol car is over £2,000 more expensive. Savings don’t stop after the point of purchase: Norwegian e-vehicle drivers can save over £3,000 a year from road toll exemptions, road tax savings and other government interventions. In the US, tax credits from $2,500-$7,500 are being offered for new electric vehicle purchases, but the credits will only be available until 200,000 vehicles have been sold each manufacturer, at which point the credit begins to phase out for that manufacturer – hardly long-term thinking by government for the vehicle owning US citizen. As we’ve seen from the riots in France last week, care must be taken when using tax incentives to tackle climate change. The proposed 3% fuel tax increase sparked widespread anger, particularly amongst those living in rural locations who rely on their car for work. The move was seen by many to punish car users without any viable, affordable alternative.

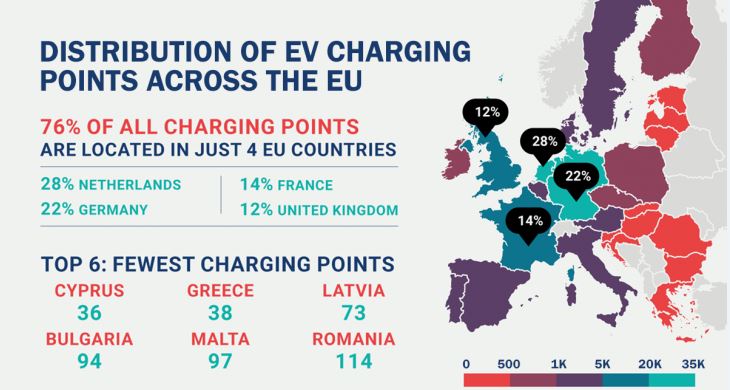

Severe lack and uneven distribution of charging points is also putting consumers off buying electric vehicles. As the diagram above shows, over three quarters of charging points in the EU are located in just four countries. On the other end of the spectrum, a large country like Romania - roughly six times bigger than the Netherlands – contains just 0.1% of the EU total.

The lack of an evenly distributed network of charging points is due to a huge lack of investment from government and business alike. The EU’s Directive on Alternative Fuel Infrastructure set clear objectives for all 28 member states in 2014, but to date implementation from governments remains very poor. As well as criticising the target of no new e-vehicle sales by 2014, the BEIS select committee also criticised the UK Government’s cuts to subsidies and the lack of charging points. More charging stations are needed nationwide, particularly in residential areas without private parking facilities.

A e-vision for the future?

E-mobility is of course not just limited to cars, vans and lorries. Electric drivetrains are transforming personal modes of transport like bicycles and scooters. On a recent trip to Paris, I made good use of the new e-scooters to get around the city, though due to the lack of safety enforcement, they are quickly being banned in cities across the world, including in Madrid last week. If you’re reading this in the UK and fancy trying e-scooters for yourself, they are available in the Olympic Park in Stratford (but banned in the rest of London!)

Perhaps where the biggest change could come is the smart incorporation of e-mobility in to the urban design and planning process. On their website, Volvo ask; ‘imagine indoor bus stops at hospitals or shopping malls,’ - e-transport could well revolutionise urban accessibility. If strict congestion and pollution laws are enacted, cities may well have to rethink vehicle densities, which could force improved infrastructure for electric public transport and personal e-transport. Or perhaps instead of reduced vehicle numbers, urban centres could be completely reconfigured for electric autonomous vehicles (AVs); Ocado has trialled a ‘milk float’ autonomous shopping delivery system in London, indicating the potential for AVs to transform last mile deliveries in retail. Other forms of transport like Hyperloop and electric air transport, akin to Uber's Elevate project, show that innovative new e-transport methods are clearly an area where sci-fi fantasies could well become reality in a galaxy not-so-far, far away.

Electromobility has a lot of scope for widespread decarbonisation and a change to the way urban areas function, but it is still very much in its infancy - particularly in developing nations. It goes without saying that for truly sustainable transport systems, the energy generation infrastructure will have to transition to renewable sources alongside the roll out of e-vehicles. Governments must work together and move from the low road to high road of policy making to encourage bold, decisive action from civic society and business. Tech is seen by some commentators as a ‘silver bullet’ solution to climate problems, and although there are climate-friendly tech solutions, real global scale change will only happen through urgent action across all three of the key topic areas the Polish Presidency has identified at COP24 – technology, humans and nature. Hopefully, in 2050, we won’t be looking in the rear-view mirror of e-mobility progress, wondering why we didn’t change up a gear sooner.

This blog is part of a series of responses to climate change and environmental breakdown being produced by the RSA for COP24

Related articles

-

A design revolution for the climate emergency

Joanna Choukeir

Joanna Choukeir on Design for Planet, the global gathering of designers during COP26, and the changes design must make.

-

A sustainable future for food, health and planet?

Elliot Kett

How does the UK build upon the EAT-Lancet Commission report? The RSA Food, Farming & Countryside Commission and City University’s Food Thinkers Seminars are presenting UK-specific modelling data and convening a panel of experts from food policy, farming, public health and government backgrounds to discuss.

-

The Eat-Lancet Commission report: my favourite eight take-aways

Sue Pritchard

Sue Pritchard comments on the EAT-Lancet Commission report on healthy diets from sustainable food systems

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.