Globally, we are reliant on just 12 plants and 5 animals for more than 75 percent of the food we eat. In recent decades, we have been extremely successful in increasing the amount of food we produce, far exceeding population growth, but are we also undermining the planets capacity to support us? As part of the drive to increase yields, farmers have been ditching local varieties of cattle and crop for more genetically homogenous varieties. With the disappearance of agricultural diversity, the unharvested species of flora and fauna that rely on ecosystem diversity disappear as well. What consequences does this have not just on the planetary systems that support us but on our health?

It starts with a banana

As you peel back the skin of that famous 'exotic' fruit we all love to buy from the supermarket, you may be forgiven for not knowing its genesis in the garden of an English stately home. Most of the bananas eaten in the developed world come from a single clone of a Cavendish banana plant grown 180 years ago by head gardener Joseph Paxton of Chatsworth House, Derbyshire. It’s this genetic homogeneity which now threatens the 5 billion Cavendish bananas we eat every year in the UK, at risk from a fungal disease that is diminishing yields globally.

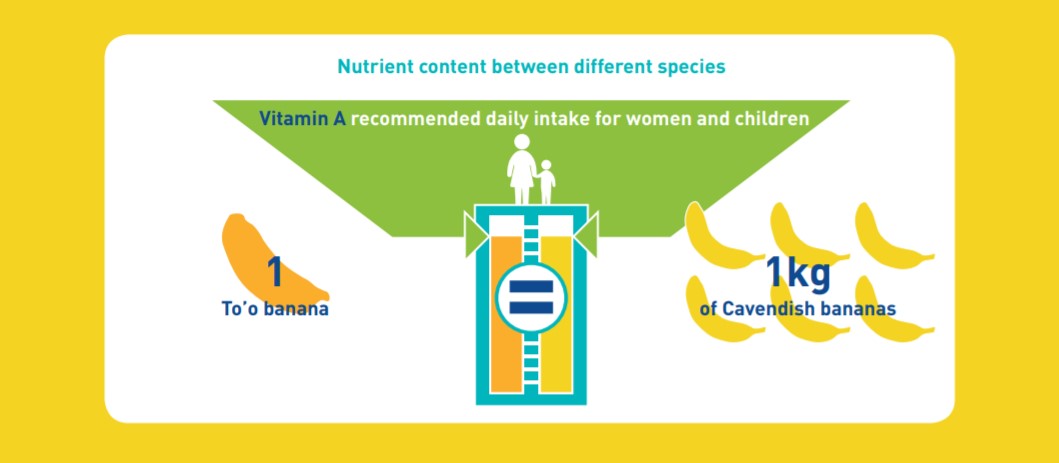

It’s not that a lack of genetic diversity is just undermining our food security, it turns out it’s not the best for our health either. One in three people in the world suffer from micro nutrient deficiency, meaning the food they are eating is lacking the key vitamins and nutrients needed to sustain good health and development. We are growing 22 percent less than we need of the fruits, vegetables, nuts and seeds to meet the global human populations nutritional requirements. And despite successes in growing more food than population growth over the last few decades, over 800 million people remain undernourished. When it comes to sources of vitamin A, it turns out there’s a much better banana than the Cavendish for the job. The To’o banana - where one banana is enough to meet a person’s daily requirement of Vitamin A, it would take a kilo of Cavendish bananas to do the same.

From microbiome to biome

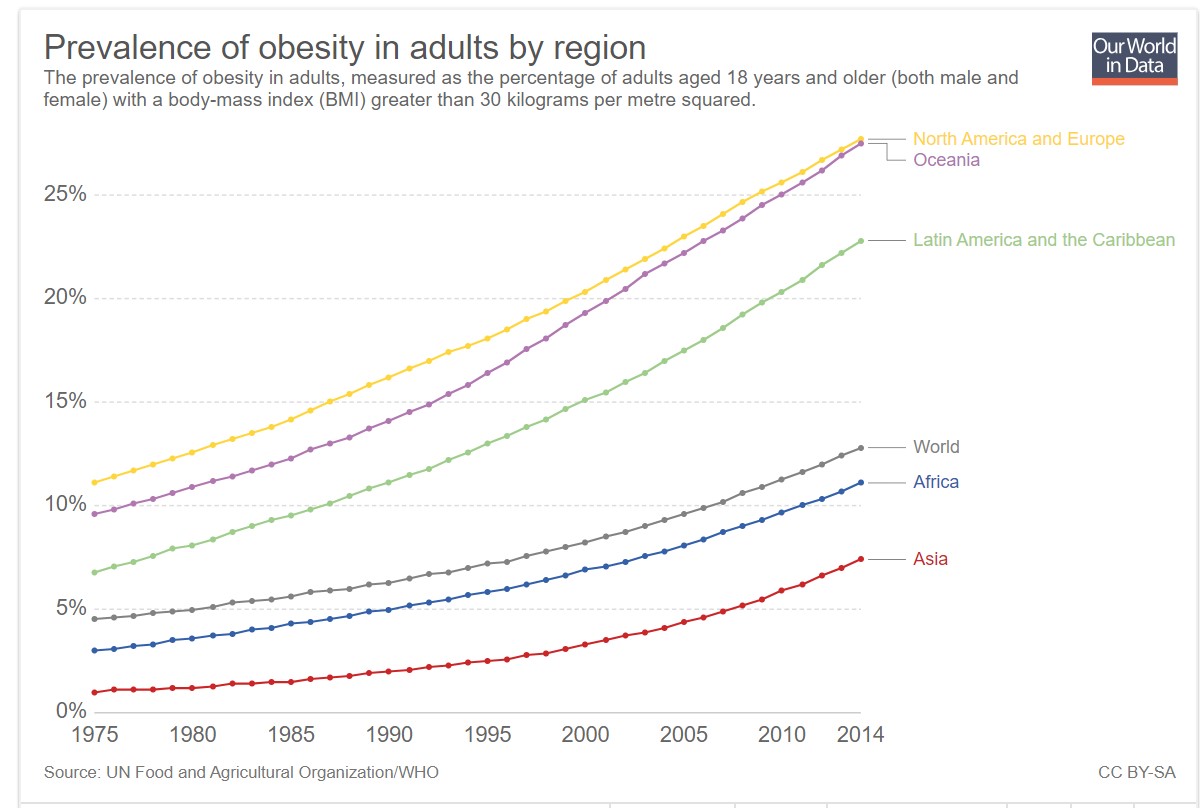

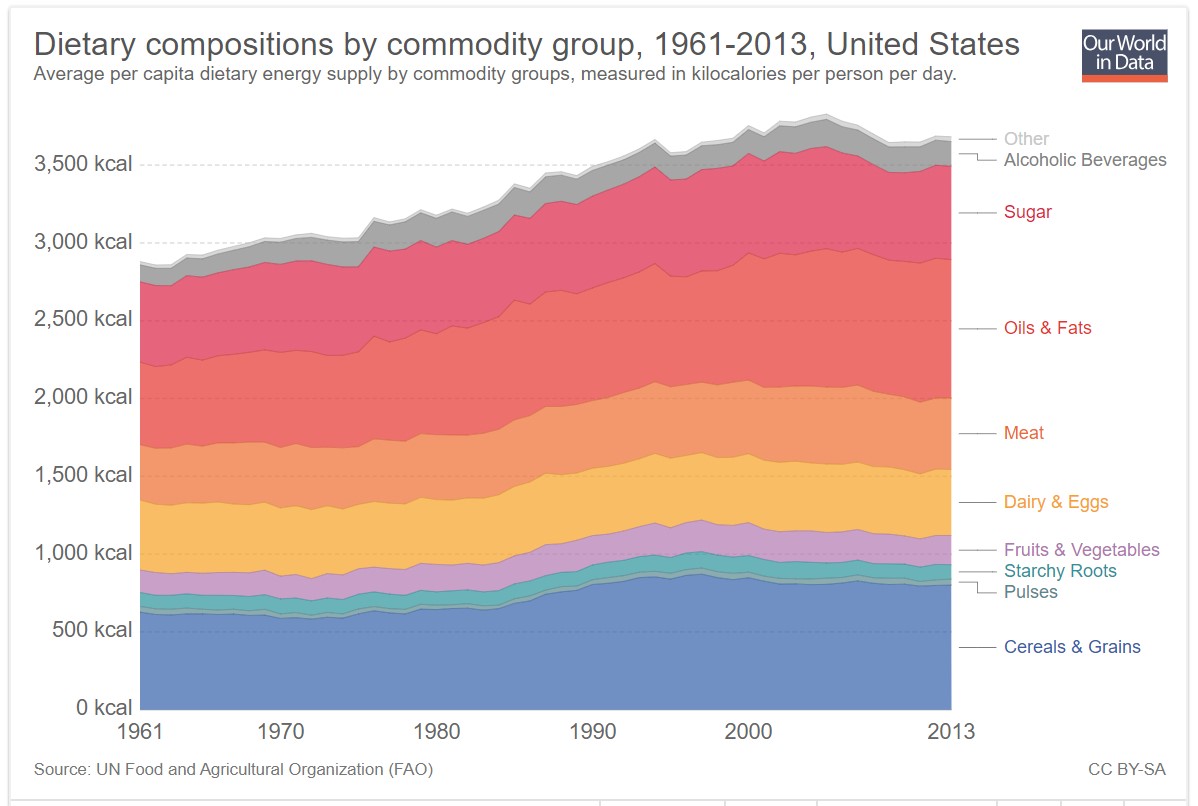

As well as micro nutrient deficiency, there is now evidence of a link between the lack of diversity in our gut bacteria, our microbiome and a whole host of diet related health issues such as obesity and type 2 diabetes. The science of our microbiome is complex, with numerous factors influencing its health, but it does seem that there is a strong connection between microbiome health and a diverse diet. Could it be that our inner gut health is reflecting the trends we’ve seen in agriculture and the world around us with a homogenisation of the foods we grow and therefore eat? Part of the picture of shifting diets in recent years has been the global trend towards greater urbanisation which leads to greater demand for convenience and processed foods. In the graph below, we see how, in US diets over the last 50 years, the biggest change has been an increase in grains and cereals and oils and fats.

While the evidence is still emerging, it’s important for us to explore in more depth how we move towards a food system that better aligns human and planetary health - The House of Lords Select Committee have recently set up an inquiry to do just this. Mary Creagh, Chair of the Environmental Audit Committee who launched the inquiry stated, “Human beings do not exist in a vacuum: we depend on this planet for everything.” Can we begin to view ourselves as part of a wider ecology, our health and sustainability may depend on it?

Biting the hand that feeds us?

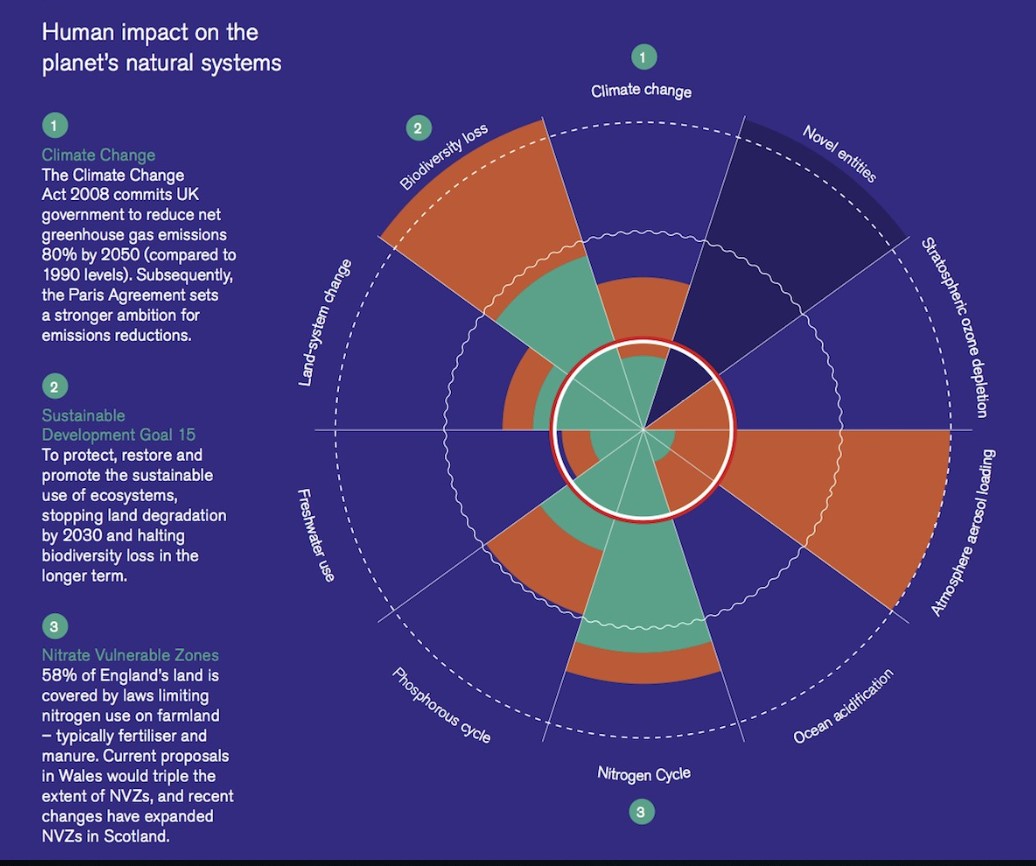

Are we destroying the planets ability to support us? In the last 50 years almost 60 percent of UK species have declined, and 15 percent are currently threatened with extinction. Years of urbanisation, industrialisation and intensive farming have left the UK in poor company globally - the 2016 State of the Nature report ranked the UK 189th in the world for biodiversity intactness. Rockstrom’s work on planetary boundaries, the limits to which Earth’s systems can safely operate show we may have already massively overreached the planet’s ability to meet social needs when it comes to biodiversity loss (see graph below). It’s estimated that rates of extinction are currently 1,000 to 10,000 times that of what they should naturally be. With agriculture in the UK accounting for almost 70% of land use, clearly how we farm has a big impact on our ability to maintain biodiversity and t live within other planetary boundaries.

Eating biodiversity

At the Oxford Real Farming Conference earlier this year, Tim Lang, Professor of Food Policy at City University made the call for us to “get biodiversity into the fields, and down our throats”. To ensure biodiversity is maintained we need to eat it. Our food security depends on genetic diversity in the long term and, with the links starting to emerge in public health circles between diversity of the microbiome and a whole host of diet related diseases, we can no longer ignore the connections between the planet’s health and our own.

Deep inside a mountain in the permafrost between Norway and the North Pole lies the Global Seed vault. It’s a backup of global seed biodiversity, an ‘apocalypse-averting’ measure with capacity for over 2.5 billion seeds. Built to survive the most extreme conditions, even this safe haven of biodiversity has been under threat, as a result of unexpected melting of the permafrost earlier this year. It’s a sombre reminder of the consequences of knocking out of kilter the fragile interconnections that keep our planet in balance.

Last week COP24 kicked off with one of its key aims to develop a synergic view of the three UN key conventions on climate, biodiversity and desertification. Michael Gove in his recent climate change speech also made the connection between climate change and environmental policy, “it is impossible to meet climate mitigation and climate adaptation objectives without the natural environment, and we can’t save nature without tackling climate change.” With agriculture playing such a large role in global land use and the associated impacts on greenhouse gas emissions and biodiversity, it has a vital role to play in maintaining the natural world – and that includes us and our health. We must act now. Aligning the needs of planet and people, we can make the changes to our food system that regenerate human and planetary health for the wellbeing of future generations.

This blog is part of a series of responses to climate change and environmental breakdown being produced by the RSA for COP24

Related articles

-

A sustainable future for food, health and planet?

Elliot Kett

How does the UK build upon the EAT-Lancet Commission report? The RSA Food, Farming & Countryside Commission and City University’s Food Thinkers Seminars are presenting UK-specific modelling data and convening a panel of experts from food policy, farming, public health and government backgrounds to discuss.

-

The Eat-Lancet Commission report: my favourite eight take-aways

Sue Pritchard

Sue Pritchard comments on the EAT-Lancet Commission report on healthy diets from sustainable food systems

-

Our Common Ground

Sir Ian Cheshire

Our Common Ground, a new progress report from the RSA Food, Farming and Countryside Commission's emerging thinking as we reach the half way point of our inquiry

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.