With 1 in 4 people worldwide now using Facebook, Twitter and Instagram there has been intense debate into what effect this is having, particularly amongst young people, with reports linking overexposure to social media with emotional distress and mental illness. Public services have been inconsistent in their efforts to keep up with these changes. Responding to this, the RSA has embarked on a social media listening exercise to understand how young people talk about mental health online. We point to new potential responses from statutory and community services in providing relevant and timely support for young people online.

Looking at how we use social media, the pace of change in contemporary society has often outstripped our ability to understand the effect of that change while it is occurring.

Social media and digital technologies are now an integral part of the lives of young people (99% of 12 – 15-year olds in the UK report being active online for over 21 hours a week): there is an urgent need for public services to better comprehend and consider how to engage with this new phenomenon.

The fast pace of change in how we interact digitally reflects what Eddie Obeng imagines as ‘world after midnight’ responses. But the first step, as RSA research highlights, is listening to the concerns of young people, and bridging the current divide whereby mental health services and young people are not ‘talking the same language’.

Will an online A&E mental health service become unavoidable?

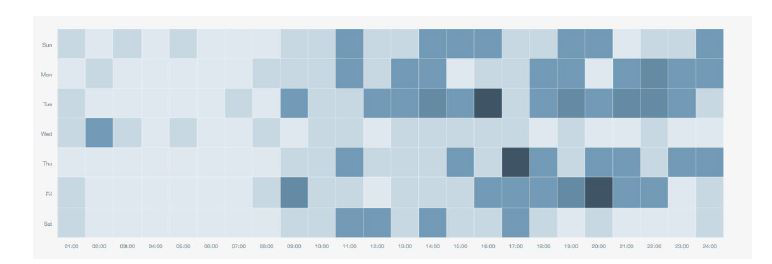

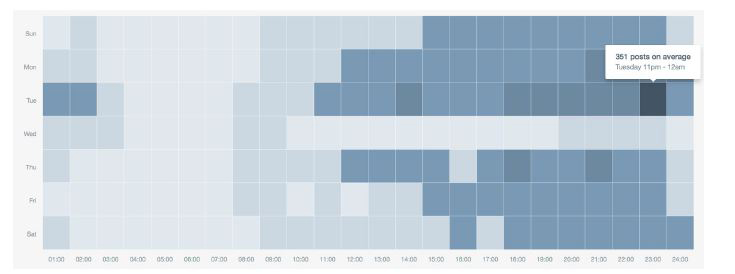

Social media listening exercises have their limitations. However, the RSA’s exercise builds upon the existing evidence base while highlighting a large gap in the current literature. Our research has identified various themes of conversation related to mental health; the demographic split within people under 25 years old; times within a typical week when conversations are most prevalent; and areas where services can improve engagement with young people.

The exercise focused on listening to the conversations of young people living in Greater Manchester and made comparisons with the national picture to identify ways in which services can better interact with young people experiencing mental health problems.

Greater Manchester was selected for several reasons, the most prominent of which was The Resilience Hub, set up after the Arena bombing in 2017, which has been highly valued as one of the best services of its kind in the country, serving anyone affected by the bombing. The Hub has demonstrated, as recognised by the Kerslake Review, the benefits of good communication and engagement techniques to identify those who may need their service, particularly young people.

The RSA’s listening exercise identified 3,800 unique social media users participating in conversations using specific terms relevant to mental health, between 16th July 2017 and 9th May 2018, which made up 3% of the UK conversation.

We found that 75% of all mental health conversations across the main social networking sites were being generated from those aged between 14-25 years old. A further 75% of the conversations online in Greater Manchester were between young people aged 19-24-year old. Search terms that drove the conversations were: depression, sleep, suicide and anxiety. Sleep and tiredness were persistent themes in connection with young people’s mental health.

1. Greater Manchester conversation by volume

2. UK conversation by volume

Less heat, more light

Throughout the exercise there was evidence of large numbers of young people seeking peer-support and sharing resources. However, amongst meaningful resources for first-hand accounts of mental illness, which help readers understand what services and support is available, we found many widely-shared blogs, articles and websites serving commercial interests which provided advice that would not stand up to expert scrutiny.

We found authoritative, impartial advice about treatment and signs and symptoms of mental illnesses hard to come by. As such, many of these sources acted to shed more ‘heat’ than light on the issues being raised by young people.

Of 3,800 conversations, we identified a range of different themes, the most prevalent of which, for both genders, was depression. Conversations around suicide were mainly generated by young men. We also found strong engagement from organisations such as Anxiety UK, who were notable in being one of the few third sector organisations that has content widely shared by young people in Greater Manchester.

Overall, the listening exercise reflects the nuanced picture evidenced in The Royal Society for Public Health’s Status of Mind report. The report reflects how social networking sites can be both a source of connection and self-exploration and a site of isolation and sharp, damaging peer-comparison. Over-exposure appears to be the significant issue.

However, the ability for young people to confront issues more traditionally identified as taboo is a significant boon. We found that social media can allow young people to talk about mental health problems openly online with peers when they might initially arise, rather than at the point of a referral to a service. Tumblr, discounted from our analysis due the inability to geo-locate posts, has consistently been highlighted as a rich source of comfort for some, particularly for young people talking about and living with conditions such as body dysmorphia.

Whilst there are risks online, overall the evidence suggests that the social media environment is as complex as face-to-face interaction. Just as we have core public services delivering interventions via A&E, the time may have come to act earlier and directly where young people discuss mental health in order to tackle the confusing and at times unhelpful information about mental health that many young people are being exposed to online.

Listen and learn

Our listening exercise suggests that the digital worlds that young people operate in hold both risks and opportunities. A social media emergency service may be something that will become necessary in order to increase the access of quality of information and support on offer for young people.

Social media can be a place where an equal measure of peer-support and clinicial best practice can co-exist. First, we need to listen.

Follow the author at @_Tom_Harrison

Related articles

-

Using economic strategies to improve health outcomes

Ian Burbidge

Ian Burbidge on the importance of an inclusive economy that provides equitable healthcare to the public.

-

Thinking about the future differently

Ella Firebrace

To solve today’s challenges, we need to think long-term. How can we do that?

-

A healthy economy?

Ian Burbidge Will Grimond

Covid shows us how our health and the economy are linked. Politics has been slow to catch up on the connection.

Join the discussion

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.

Very useful for those of us struggling to grasp the impact and potential of social media on mental health and as a channel for support and support services. We see the negative impact of social media in our client caseload at www.thelowdown.org but struggle to understand how it is being used to access information or as an alternative to traditional mental health support services, on or off-line. We need more of this research to better understand usage, raise awareness and inform a debate. Thankyou.