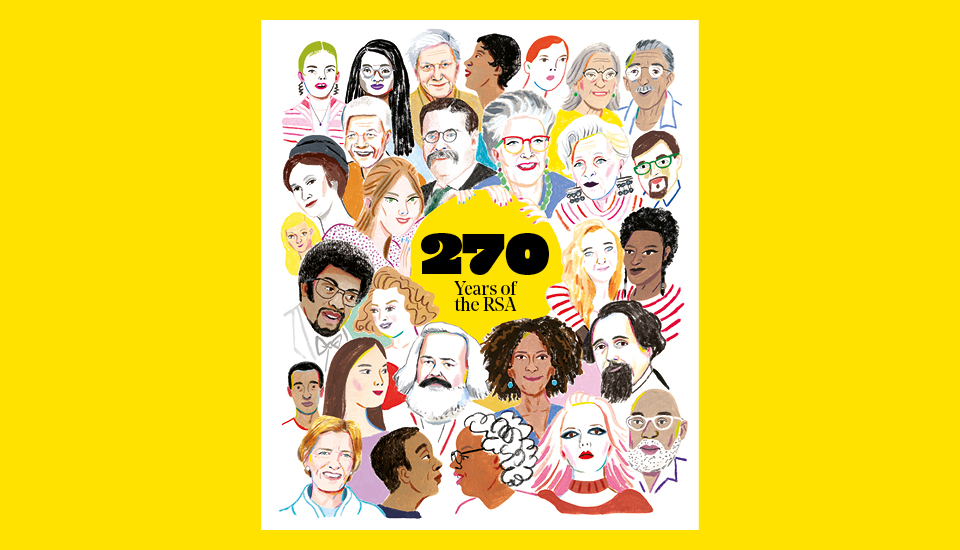

The Society celebrates its 270th birthday on 22 March. But what if it had never been born?

Imagine an RSA Fellow, excited for the upcoming events to mark the Society’s anniversary, falling asleep in their chair with the RSA Journal in hand, and dreaming of waking up in a parallel universe in which the institution had never existed.

Tracing their usual way to RSA House on London’s John Adam Street as though on autopilot, our sleepy Fellow walked through Trafalgar Square — and was immediately struck by the sight of the fourth plinth. Instead of the usual rotating exhibits of contemporary sculpture, there was a stolid but unremarkable statue of Elizabeth II — just one more bronze figure blending in with the generals and her great-great-great uncle on the other plinths, and largely ignored by the thousands walking past.

It made sense, they remembered — the restaurateur and Great British Bake Off judge Prue Leith would never have been Chair of the RSA. And that meant she would never have regularly taken taxis to its building past Trafalgar Square, where she noticed a bare plinth. She would never have compelled the RSA to campaign for the plinth to be used to promote works of contemporary sculpture, and to oversee the idea trialled. And, without those trials, the mayor of London would never have been inspired to make the Fourth Plinth programme permanent.

Making their way down the Strand towards RSA House, our Fellow frowned and looked up again at the buildings. Many more than they remembered were of concrete and glass. Where was all the stone and brick? Turning off the Strand, eyes failing to find the blue plaques commemorating the artist Thomas Rowlandson and inventor Richard Arkwright, it was obvious why. The RSA had initiated the memorial tablets scheme in the 1860s not only to remind Londoners of their history, but to prevent many of the buildings being torn down. Although it had been only partially successful in the early years, the absence of the scheme for almost two centuries, never to be taken on by London County Council or English Heritage, had diminished preservation and shifted the architectural make-up of the city towards the modern.

Similarly, without the RSA’s campaigns to preserve older private dwellings in the 1920s and 30s, many Victorian, Edwardian and neo-Elizabethan improvers had had their way. In the early 20th century, the RSA served as a hub for preservation movements all over the country, with this Journal as its gazette, but with it never having existed, much of the country’s architectural heritage was simply… gone.

Coming up to where the entrance to RSA House ought to be, our Fellow stopped short, their morning fix of caffeine finally having an effect. Instead of RSA House, there stood a neoclassical church. Of course. The Adam brothers, who had designed the surrounding streets in the 18th century, had intended for there to be a public building in their development, and RSA House fitted that bill. Without an RSA to accommodate it, however, a church had been built instead.

Signal problems

At something of a loss of what to do, our Fellow checked their phone to see what appointments they had made that day — might as well give them a try.

But the phone was different. It was markedly slow and seemed to struggle with finding a signal. Our Fellow considered for a moment. The RSA had been vital to the history of telecommunications: the place where Carl Wilhelm Siemens had first seen the remarkable insulating properties of a naturally occurring latex from the sap of a tree found in Malaysia, — gutta percha — which was sent to London by one of its members based in Singapore. Without that spark of inspiration, Siemens had never gone into business with his brothers to insulate underwater electric telegraph cables. Near-instantaneous communications across continents, even just between Britain and France, had been delayed by decades.

In the late 19th century, the RSA was also an important meeting place for the pioneers of electrical inventions, hosting early demonstrations of William Fothergill Cooke’s electric telegraph and Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone, and lectures on long-distance radio by Guglielmo Marconi, as well as the first public demonstrations in England of Thomas Edison’s incandescent light bulb and, in 1920, of Frederick G Creed’s teleprinting by wireless. Without that meeting place for inventors, and without that platform for new technologies, the development of telecommunications had been slowed in its infancy, even if it had not stopped.

And the phone was clunky. Really clunky. It suddenly dawned on our Fellow that without the RSA there had been no Student Design Awards, and so, over the course of a full century, a great many iconic designers had never had the same experiences and opportunities for research. Jony Ive had never won a travel grant to San Francisco and fallen in love with it, and had never ended up working for Apple. Instead, he found inspiration elsewhere, and iPods, iMacs, iPhones, iPads and the like, with their clean simplicity, had never set the pace for design.

Looking around with fresh eyes, the Fellow began to notice many more ways in which this alternative reality felt a bit off. Yes, the world had a different aesthetic. The street signs, bus interiors and car shapes just seemed to lack something. They were clunkier, less useful. Drabber, somehow, and less pleasing to the eye.

Missing museums

But with an appointment in the calendar — a meeting just south of Hyde Park — our Fellow had no more time to waste. Hopping on the District Line, they looked for their stop. But it wasn’t there. Between Sloane Square and Gloucester Road it said only… Brompton? All became clear when they arrived and walked outside, heading north to find the address. Where there should have been the magnificent Natural History Museum, the Victoria & Albert Museum, the Science Museum, the Royal Albert Hall, the Royal College of Music — all of the cultural institutions of Exhibition Road, really — there was simply row upon row of concrete apartment blocks.

Without the Great Exhibition, the progress of internationalisation had been markedly slowed.

Without the RSA there had been no Great Exhibition of 1851, and thus no profits with which to create the agglomeration of cultural institutions that came to be known as ‘Albertopolis’, after its figurehead, the consort of Queen Victoria, Prince Albert. Henry Cole, the driving force behind the Great Exhibition, had never coined the term ‘South Kensington’ as the name of his new museum, which later became the V&A. Indeed, that museum collection had never been assembled at all, and many of the others had ended up dispersed. The museum’s effect on design had never been felt — perhaps another contributor to the city’s overall lacklustre appearance.

Come to think of it, our Fellow realised, there also really hadn’t been all that many tourists in Trafalgar Square that morning. And there were none at all in Brompton, with little there to attract them. A sudden thought occurred, and our Fellow quickly checked the rate to call someone in another country, or to send a package internationally. What came up was a mess of complicated infographics and tables, along with some eye-watering prices. It was just as they had suspected. Without the Great Exhibition, the progress of internationalisation had been markedly slowed. There were higher trade barriers, less standardised postage and telephone rates, and far more difficult travel and migration arrangements between countries.

The RSA had also used its prizes... to reward generations of young artists, particularly women.

Many of the conversations about standardisation and internationalisation that had begun at that event had instead only been embarked upon more gradually, and much later. And the friendly competition between countries to hold subsequent exhibitions, hoping to outshine the Great Exhibition’s Crystal Palace, also never got going in quite the same way. Yup, a quick search confirmed it — the entrance to the 1889 World’s Fair, the structure we know today as the Eiffel Tower, had never been built.

Absent artists

Their meeting concluded, but having been denied a visit to a South Kensington museum nearby, our Fellow decided to travel a bit further, to Tate Britain. After all, it was likely to be much emptier than usual, with so many fewer tourists in this reality. But even this was a shock. A great many of the paintings by British artists were missing, with the late 18th and 19th centuries looking especially sparse. On reflection, however, it made sense.

The RSA had provided a crucial platform for artists in the 18th century: by holding the country’s first dedicated exhibitions of contemporary art from 1760 onwards — the precursor to the Royal Academy’s annual exhibitions — the RSA had helped artists develop their styles for the public, and expose their works to a wider set of patrons. And it was out of the group of artists involved that the Royal Academy had eventually formed (though after falling out with the RSA over how the exhibitions should be run).

The RSA had also used its prizes, since its very first meeting, to reward generations of young artists, particularly women — not only to become professional artists themselves, but to develop a general taste and appreciation for art, which would lead them to become patrons in later life. Without all these decades upon decades of support, our Fellow found 19th-century British art in the alternative reality was notably lacking, with repercussions for later periods, too. In the 1840s, the RSA served as a hub for a community that experimented with and developed photography, and had hosted the first exhibition of photography in 1853. In this bleaker reality, that group had never assembled and that exhibition had never happened, and so the Royal Photographic Society had never been formed.

Many of the conversations about standardisation and internationalisation that had begun at that event had instead only been embarked upon more gradually, and much later. And the friendly competition between countries to hold subsequent exhibitions, hoping to outshine the Great Exhibition’s Crystal Palace, also never got going in quite the same way. Yup, a quick search confirmed it — the entrance to the 1889 World’s Fair, the structure we know today as the Eiffel Tower, had never been built.

Smaller cities

And then there was the relative lack of people. It wasn’t just the tourists — the city felt generally smaller, less busy. What could explain it? Might it be because the country had never enjoyed the effects of the RSA’s prizes for agricultural innovations? The absence of a century’s worth of turnip-cutting machines, novel ploughs, schemes for transporting fresh fish to market, and experiments on the best feed for cattle in winter must presumably have had a long-term effect on slowing the rise of agricultural productivity.

It had not stopped that progress short, of course, but over the previous two centuries British cities had not been able to grow at the rate they otherwise would have, requiring more people to continue their back-breaking labour in the fields; the country’s population as a whole had not been able to grow as quickly. Given how many agricultural innovations were also shared with the rest of the world, thought our Fellow, it wouldn’t be surprising if the global population was also much lower than in their own reality.

It was a troubling thought, but with evening approaching, our Fellow needed to get to Birkbeck University for their evening class. Except that, when they arrived, it wasn’t there. After all, Birkbeck was originally the London Mechanics’ Institution, set up for workers’ education, and one of many educational institutions for and often run by workers. The RSA had never created the Union of Mechanics’ Institutions — a network set up to support them — which breathed new life into the movement in the 1850s when they were widely thought to be in decline, and the institution had become a victim of this decline.

In fact, the Fellow realised, the RSA Journal itself, currently sitting on their coffee table at home, was originally created as the union’s newsletter, with the RSA serving as its hub. And it was from the RSA serving the needs of the mechanics’ institutions that public examinations were born.

Exam failings

Our Fellow quickly looked it up to check: because the RSA had never set up its public examinations, these examinations had never been co-opted by the government —with the RSA often trialling new subjects before the government then adopted them — and whole swathes of the state education system had thus simply never come into being. The exam board OCR certainly did not exist, as none of the letters in the acronym had ever come into being: the examination boards set up in the 1850s for the universities of Oxford and Cambridge (the O and C), which had both been inspired by the R (the RSA).

The lack of an RSA had impacted education in other ways too. Girls’ secondary education was lagging far behind that of boys: Maria Grey had never been able to use the RSA as a platform to eventually create the Girls’ Public Day School Trust, which in the early 20th century was responsible for educating much of the first generation of women to attend British universities. A great many technical qualifications, such as those offered by City & Guilds, had also never come into being.

The guilds had never been urged to take on new educational roles in the 1870s, which they initially did by funding the RSA’s examinations and, later, by taking over the running of the technical ones. And there had been less encouragement from the government for education beyond the basics of teaching literacy and numeracy, as the Department of Science and Art — another outcome of the Great Exhibition, run by its instigator Henry Cole — was never set up.

Dismayed, our Fellow returned home, with little else left to try. And then started awake, on their chair, the RSA Journal having just slipped from their grasp.

Anton Howes is the RSA’s Historian in Residence, and the author of Arts and Minds: How the Royal Society of Arts Changed a Nation, a history of the RSA from its founding to the present day.

Become an RSA Fellow

The RSA Fellowship is a unique global network of changemakers enabling people, places and the planet to flourish. We invite you to be part of this change.

RSA Journal Issue 1 2024

Journal

Enjoyed this feature? Read other pieces from the 270th-anniversary edition of the RSA Journal.

Join the conversation

Circle

Has this Journal feature piqued your interest? Are you an RSA Fellow? Why not share your thoughts with the wider RSA community? Head over to the dedicated Journal space on Circle to chat with other changemakers.

Read other RSA Journal features

-

Soul conversations

Feature

Judah Armani

A designer’s unorthodox approach is transforming the way education is delivered in prisons across the UK and in the US.

-

Young at heart

Feature

Jonathan Rosser

Becoming a nation with children at its centre in 10 courageous steps.

-

King Cole’s blue-sky thinking

Feature

Mike Thatcher

Sir Henry Cole’s list of achievements is long and varied — from the first director of the V&A to helping to establish the Great Exhibition. So it is only right that ‘King Cole’ is commemorated by a blue plaque where he lived and worked in London’s South Kensington.

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.