Cliff Pelham FRSA argues we need to introduce new local, democratic platforms for electors and their representatives.

Parliamentary democracy may be the least-bad form of governance but it will never be easy. As humankind struggles to come of age and to acknowledge that its stewardship of the planet rests upon an obligation to actively pursue the common good, would-be tyrants and the unthinking mob stand ever ready to destroy trust in the vulnerable institutions upon which democracy depends.

Almost a century has passed since universal suffrage was adopted in the UK and the time has surely come to ask if the rampant adversarial and majoritarian behaviour that this emboldened should now be tempered by further reform.

Democracy cannot survive a loss of trust in the practice of politics. Trust is being lost because policy rivalry has been pushed aside by competition for votes: forgetting that the ballot confers legitimacy but does not bestow wisdom. Current and aspiring representatives need to hear and understand their constituents’ present thinking and state of mind, in order to effectively explain their policies and fully appreciate the impact of them; lacking openly-voiced advice, false assumptions and spectacular misjudgements too often ensue.

UK citizens currently have no greater role to play in governance than the one they had when most women won the vote in 1918; this despite secondary education for all (1945) and now most school-leavers moving into tertiary education, mass communication by radio (1920s), television (1950s) and the arrival of the digital age. Citizens are treated as if they have no capacity or desire to have a view, whilst having to find their way through deceitful propaganda, dubious 'consultations' and social media mischief. Evidence from their experience is presently too easily ignored with impunity.

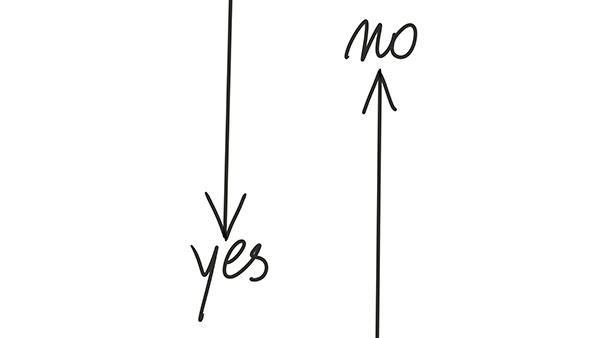

At present the Westminster system of politics, governance and law are dominated by adversarial processes. There is need for a counterbalancing inquisitorial element to be introduced. This means developing practices that ensure that all relevant views and knowledge, and all questions arising from them, are sourced and made available to all citizens who might be affected, in a non-partisan way. It means creating 'knowledge-in-common' before considering what might be done: a mutually informative and educative as well as political purpose not beholden to mass or social media.

Constituency platforms

Experience has taught that citizens best assert their power by way of representation in an elected assembly chosen through a robust and respected system of voting. Any additional system aimed at enabling citizens to contribute their influence between elections must be designed to be compatible with this. As parliamentary representation is organised by way of constituencies it would be logical to organise influential activity likewise, with the direct involvement of current and aspiring parliamentary and local government representatives on a fully cross-party (and non) basis.

To gain popular acceptance, this would work best if managed ‘locally’ – at a level seen by citizens as appropriate to their sense of locality and meaningful reciprocal obligations – while being at such a scale as to attract time and assistance from willing local and external advisors, and to justify the resources needed. Parliamentary constituencies, as the constitutionally-primary point of contact between individuals and government, would thus seem to be the natural place to locate a new democratic platform.

Once established, such ‘constituency platforms’ would be available for interaction with the current and any future local/regional/devolved systems of governance, as well as for locally-defined communal purposes. There are numerous off and on-line participative techniques now being used and evaluated worldwide for each prospective ‘constituency platform’ to draw upon and adapt to their local purpose. There may well be a role for an enhanced adult education sector here; however, merely grafting new techniques onto the existing, underdeveloped democratic system will not suffice.

How might this work in practice? Most citizens have limited time and energy to devote to political affairs; and introducing any new inquisitorial/influencing process must be guarded from falling into the hands of vested interests, idealogues and lobbyists. Therefore, establishing, and subsequently governing, a platform should be in the hands of an equal number from each of the political parties that received a significant vote at the most recent election, together with a similar number of non-aligned electors selected annually by sortition from that constituency. The party persons could be drawn from accredited party supporters: indeed exposure to experience in this role might well become seen as essential for selection as a candidate.

A constituency platform should:

- Involve all political parties active (according to an agreed criterion) in the constituency;

- Be confined to, yet include as of right, all persons on an up-to-date electoral register;

- Have a not-for-profit legal status in order to safeguard funding;

- Demonstrate that it is derived from recognised democratic thought;

- Be proofed against takeover by factions or obsessives, or extraction of data for profit;

- Uphold public-service standards of civility, and have processes to deal with defamatory or otherwise offensive material;

- Accept contributions to its activities by way of all channels (electronic and otherwise);

- Assure citizens that their situation and preferences will be given proper consideration when elected representatives are taking decisions;

- Ensure deliberations are held accountable to evidence, expose misinformation and challenge propaganda from vested interests;

- Be found rewarding by those who administer it.

This reform of democratic practice will not come about through prior legislation or top-down exhortation alone but rather by way of an accumulation of local educative initiatives; practice through which experience and expertise can be nurtured. Nor does it rule out or inhibit discussion about reform of other aspects of democratic practice. Such an approach must be introduced by local agreement and designed so as to win and secure confidence in an enhanced democratic regime and include social pressures to act honourably: vital features in a country without a written constitution.

After an early career in telecoms engineering Cliff returned to full-time education to study social sciences, majoring in economics; after which he held public-facing roles in local government and the voluntary sector developing novel political and organisational structures.

Related articles

-

Is nudging helping governments respond to Covid-19?

Comment

Chetan Choudury FRSA

Chetan Choudhury FRSA calls on more governments to adopt 'nudging' as an integral policy tool.

-

Ensuring the future of digital society

Comment

Michael Barwise FRSA

Michael Barwise FRSA on why we need to invest in engineering mindsets.

-

Be the first to write a comment

Comments

Please login to post a comment or reply

Don't have an account? Click here to register.